- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

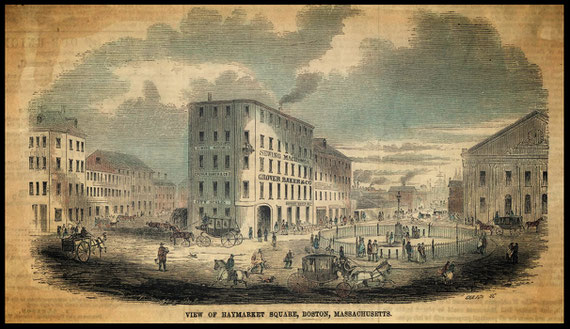

GROVER & BAKER

SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

1851 - 1875

Haymarket Square 94 Chambers Street, N.Y

Boston, Massachusetts 495 Broadway, New York

By the mid-1850s the basic elements of a successful, practical sewing machine were at hand, but the continuing court litigation over rival patent rights seemed destined to ruin the economics of the new industry. It was then that the lawyer of the Grover & Baker company, another sewing-machine manufacturer of the early 1850s, supplied the solution. Grover & Baker were manufacturing a machine that was mechanically good, for this early period.

William O. Grover was another Boston tailor, who, unlike many others, was convinced that the sewing machine was going to revolutionize his chosen trade. Although the sewing machines that he had seen were not very practical, he began in 1849 to experiment with an idea based on a new kind of stitch. His design was for a machine that would take both its threads from spools and eliminate the need to wind one thread upon a bobbin. After much experimenting, he proved that it was possible to make a seam by interlocking two threads in a succession of slipknots, but he found that building a machine to do this was a much more difficult task. It is quite surprising that while he was working on this idea, he did not stumble upon a good method to produce the single-thread (as opposed to Grover and Baker’s two-thread) chainstitch, later worked out by another. Grover was working so intently on the use of two threads that apparently no thought of forming a stitch with one thread had a chance to develop.

At this time William O. Grover became a partner with another Boston tailor, William E. Baker and on February 11, 1851, Grover & Baker were issued patent US 7.931 for a machine that did exactly what Grover had set out to do; it made a double chainstitch with two threads both carried on ordinary thread spools. The machine used a vertical eye-pointed needle for the top thread and a horizontal needle for the underthread. The cloth was placed on the horizontal platform or table, which had a hole for the entry of the vertical needle. When this needle passed through the cloth, it formed a loop on the underside. The horizontal needle passed through this loop forming another loop beyond, which was retained until the redescending vertical needle enchained it, and the process repeated. The slack in the needle thread was controlled by means of a spring guide. The cloth was fed by feeding rolls and a band.

A company was organized under the name of Grover & Baker Sewing Machine Company and soon the partners took Jacob Weatherill, mechanic, and Orlando B. Potter , lawyer (who became the president), into the firm.

Potter contributed his ability as a lawyer in lieu of a financial investment and handled the several succeeding patents of Grover & Baker. These patents were primarily for mechanical improvements such as patent US 9.053 issued to Grover & Baker on June 22, 1852, for devising a curved upper needle and an under looper to form the double-looped stitch which became known as the Grover & Baker stitch.

One of the more interesting of the patents, however, was for the box or sewing case for which Grover was issued patent US 14.956 on May 27, 1856. The inventor stated “that when open the box shall constitute the bed for the machine to be operated upon, and hanging the machine thereto to facilitate oiling, cleansing, and repairs without removing the machine from the box.”

It was the first portable sewing machine.

By 1857 Grover & Baker had opened a showroom at No. 495 Broadway. Their machines were not only functional, but decorative. The cast iron bases were ornamental and the cabinetry was finely crafted.

The New-York Daily Tribune noted on January 9, 1857 "Grover, Baker & Co. employ, to a considerable extent, the cabinetwork cases by Ross & Marshall, of this city, which makes the machine an ornament and by no means the least really valuable ornament of the sitting-room."

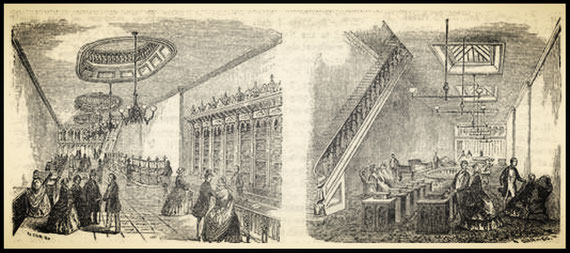

Newspaper advertisements for Grover & Baker's "Noiseless family sewing machines" began noting in September 1859 that they could be seen "temporarily at 501 Broadway." The reason for the short-term abandonment of No. 495 Broadway was that the firm was updating its building. George H. Johnson, architectural designer for Daniel Badger's Architectural Iron Works, fashioned a remarkable Gothic Revival facade for the formerly unremarkable structure.

The two ground floor windows were 14 feet high and five feet wide; each a single pane of plate glass. The second floor, where the Ladies' Parlor was located, held windows 10 feet tall. Cosmopolitan Art Journal wrote "Entering the place the observer is at once in a large and elegant sales room, twenty-five feet wide by two hundred feet long. The sales room which is elegantly furnished, is lighted by seven chandeliers, of six burners each."

Along the right side were counters and cabinets for the sale of needles, thread, and other sewing supplies. The opposite side of the selling floor displayed the sewing machines.

Upstairs, buyers were instructed on using their new machines in the Ladies' Parlor. "Skillful and obliging lady operators are in attendance, to render necessary assistance, and an hour or two generally suffices to initiate the most inexperienced into the mysteries of the whole thing."

In 1862 at the International Exhibition in South Kensington, London, about 50 types of sewing machine were on show on over 20 stands. Goodwin was the Paris agent for the Grover & Baker Co. He had a display of their machines (as did Newton Wilson) including industrials and leather stitchers. Goodwin also manufactured Grover & Baker machines under licence in Paris and held various patents himself for improvements to them.

The use of the sewing machines was put towards the war effort after rebellion erupted in the South. On November 13, 1862 The New York Times advised "The Ladies Relief Association, at the Rooms of Grover & Baker, No. 495 Broadway, ask contributions in money, or material to be made into clothing for the soldiers. Donations of yarn will be very acceptable."

Things were going extremely well for the firm. In 1865 Grover & Baker was producing 1,000 machines per week. Domestic models, called "Family Sewing Machines," ranged in price from $45 to $100.

In 1867 the company received a financial jolt when fire broke out in the cellar packing room at around 6:00 on the evening of February 22. Although firemen responded quickly and "by their energetic labors, succeeded in subduing the flames before they had reached the upper floors," as reported by The New York Times, there was $25,000 in lost stock, only $15,000 of which was insured.

But Grover & Baker had other problems to concentrate on. Despite their constant improvements, by 1870 their technology was outdated and their patent protections were expiring.

Though the Grover & Baker company manufactured machines using a shuttle and producing the more common lockstitch, both under royalty in their own name and also for other smaller companies, Potter was convinced that the Grover & Baker stitch was the one that eventually would be used in both family and commercial machines. He, as president, directed the efforts of the company to that end.

The Financial Panic of 1873 decimated sales and when the basic patents held by the “Sewing-Machine Combination” began to run out dissolving its purpose and lowering the selling price of sewing machines, the Grover & Baker company began a systematic curtailing of expenses and closing of branch offices. All the patents held by the company and the business itself were sold to another company. But the members of the Grover & Baker company fared well financially by the strategic move.

In 1875 the company merged with the Domestic Sewing Machine Co..

No. 495 Broadway was taken over by woolen cloth merchants Edson Bradley & Co. The firm was run by Edson Bradley; his son, William G. Bradley; son-in-law Hugo Hoffman; and a Mr. Church. Unfortunately, the Financial Panic dealt a disastrous blow to their company as well.

1876 PHILADELPHIA EXHIBITION

Sewing Machines awarded at the 1876 Philadelphia Exhibition

It is now generally acknowledged, tacitly or otherwise, that machines employing curved needles are only practicable for very light work. The sole machine in the Exhibition with a curved needle, after doing fairly well some light work, broke down lamentably on a heavier class of goods. We may also note that the two spool sewing machines, two of which were fully tried, were not found to stand the tests well, either for light or heavy work. As regards sewing machine attachments, no medal was given for the reason that the principal makers of the best sewing machine attachments did not appear in person; according to the rules, exhibitors of other peoples products could not be noticed; while it was preferred to ignore anything second-rate.

The Grover & Baker machine and its unique stitch did not have a great influence on the overall development of the mechanics of machine sewing. The merits of a double-looped stitch its elasticity and the taking of both threads from commercial spools were outweighed by the bulkiness of the seam and its consumption of three times as much thread as the lockstitch required. Machines making a similar type of stitch have continued in limited use in the manufacture of knit goods and other products requiring an elastic seam. But, more importantly, Grover & Baker’s astute Orlando B. Potter placed their names in the annals of sewing-machine history by his work in forming the “Combination,” believed to be the first “trust” of any prominence.

U.S. Supreme Court

Grover & Baker Sewing Machine Co. v. Radcliffe, 137 U.S. 287 (1890)

Grover and Baker Sewing Machine Company v. Radcliffe

No. 72

Argued November 13-14, 1890

Decided December 8, 1890

137 U.S. 287

The Grover and Baker Sewing Machine Company machines were awarded the Imperial Cross of the Legion of Honor at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1867 and received additional awards at other fairs and expositions. Materials in the collection include sheet music of the “Sewing Machine Gallop” (1865) and a sample of cloth with stitching done on a Grover and Baker sewing machine.

sources:

The Invention of the Sewing Machine,

by

Grace Rogers Cooper

***