- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

PEGGING MACHINES

The first large manufactory in which machinery was employed in the manufacture of boots and shoes was that established at Battersea, in England, by Sir Marc Isambard Brunel, the celebrated engineer, for the supply of shoes to the British army during the last war. The labor was performed by the Chelsea pensioners and the process employed was that of riveting the soles by double rows of small nails, the bottoms being at the same time thickly studded with copper or iron nails. The ingenious proprietor, who had a patent, contrived many other small machines for cutting out and hardening the leather by rolling, punching the holes, forming and inserting the nails, &c, some of which are still used in France. But the method appears to have fallen into disuse after the peace in 1815, probably on account of the cheapness of manual labor. The manufacture of pegged boots and shoes, which now forms the greater proportion of the work of our factories and the greatest improvement yet made in the business, as far as labor is concerned, was practiced as early as 1812 in New York and very generally in Connecticut, although this valuable invention has been ascribed to Joseph Walker, of Hopkinton, Massachusetts, about the year 1818. We find that a patent for a method of pegging boots and shoes was taken out in July, 1811, by Samuel B. Hitchcock and John Bement, of Homer, New York and another by Robert U. Richards, of Norwalk, Connecticut, in May, 1812, for the use of wooden pegs, screws, &c. Samuel Milliken, of Lexington, Massachusetts, in 1807, took out a patent for metallic bottoms for boots and shoes. A pegging machine was the subject of a patent by Nathan Leonard, of Merrimack, New Hampshire, in June, 1829 and another patent in 1833.

In 1851 was patented the ingenious machine for pegging boots and shoes by Alpheus C. Gallahue, of Metamora or Matamoras, Ohio, where it was put in practical operation. It enabled one man to peg a boot or shoe with two rows of pegs on each side in three minutes, cutting its own pegs at the same time.

In 1853 patents were issued to Gallahue for a further improvement and to seven other different persons for shoe-pegging machines.

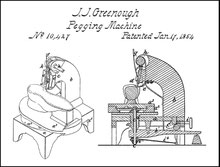

In 1854 another ingenious machine for pegging boots and shoes was issued to John James Greenough but to what extent the machine has contributed to the development process is currently unknown, anyway none of them came into general or successful use until about 1857.

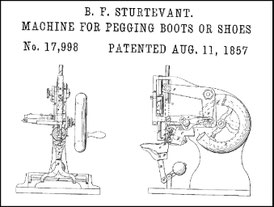

In 1857 the pegging machines of Benjamin F. Sturtevant and of Seth D. Tripp and Luther Hill have proved useful inventions. Several minor inventions have materially contributed to the extension of the pegged shoe and boot manufacture, which now constitutes at least three-fourths of the general business.

The pegging machine and the McKay machine revolutionized the industry, but did not put an end to hand shoemaking, which has continued to the present day, yet with a constantly diminishing importance. The great gain, of course, was the large increase in the number of shoes made, with a lowering of the retail price and a widening shoe market.

extract from:

1. Shoe Machinery by Frederick J. Allen 1916

2. Manufacturers of the United States 1860 Government Printing Office 1865

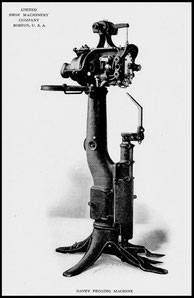

Davey Pegging Machine

This is a floor machine for attaching the soles of boots and shoes to the uppers by means of wooden pegs. The work is pegged off the last, thus effecting a great saving in the expenditure for lasts. The pegs are cut by the machine from rolls and are always uniform in size. The machine may be fitted to drive from three to six and one-half pegs to the inch, and any size or length of peg may be used. The machine drives only one row at a time, and gauges are furnished with each machine, enabling the operator to drive additional rows of pegs up to three rows. A special gauge is furnished for pegging across the butts of taps. The machine has a cutting device mounted in the tip of the horn which automatically cuts off the projecting ends of the pegs flush with the insole on the inside of the shoe as fast as the pegs are driven. This device is of the utmost importance, because it leaves the inside of the shoe absolutely smooth. The horns are supplied in various sizes suited to the requirements of the smallest shoe to the largest boot. The machine is extremely rapid in operation, and yet the work produced is unsurpassed. The saving effected by pegging off the last, the smooth insole left by the cutting device, the great capacity of the machine and the beauty of the finished product make the use of this machine of greatest advantage to the manufacturer of pegged shoes.

(Description from 1914 USMC Catalog)

The Davey Pegging Machine was one of the first machines to "come into the company" upon it's formation in 1899.

SHOE CONSTRUCTION TECHNIQUES

The Pegged Shoe

The relation between pegged and sewn shoes during the Civil War was 2:3. Means only 35% c. of footwear was pegged. The Philadelphia Depot has not issued pegged footwear at all but 3.231.647 pairs of sewn shoes. ( either machine sewn or welted )

The Machine Sewn Shoe

Blake Stitch/McKay Method

Shortly after the beginning of the Civil War the Blake Sole stitcher was invented and found wide usage during the remainder of the war. With the help of the Blake-McKay stitcher a sole was attached to the upper and inner sole by two rows of stitching. To this outer sole the final sole was stitched by hand.

The machine for Blake construction was invented in 1856 (perhaps it was patent US 20.775 July 6, 1858 ) by Lyman Reed Blake. He later sold the patent to Gordon McKay, hence the alternate name. Another child of the Industrial Revolution, it’s often referred to as a “Blake Stitch” and is less labor-intensive than Goodyear welting. This is very common on Italian shoes, which rely on the sleekness that this type of construction provides. The process is relatively simple: Upper is wrapped around the insole and these two parts are stitched to the sole. A single stitch attaches everything. No intermediate layers, no double stitches.

Pros: Less expensive than a Goodyear welted shoe but can still be resoled. Also more flexible and lightweight than Goodyear due to that absence of the welt layer. Also great for shoes that require a close-cut sole that’s flush with the upper because there are no exterior stitches.

Cons: Soles are less waterproof because the stitching allows water to seep in and the thinness of the sole wicks water into the shoe. A rubber sole would eliminate this issue, however.

The Machine Sewn Shoe

Blake Rapid Construction

Blake-Rapid construction for shoes is a hybrid of Blake and Goodyear constructions. It adds the mid-layer welt found in Goodyear welt construction but keeps the Blake-stitching technique. This is typically seen on bulkier, more rugged shoes.

Pros: More water-resistant and durable than Blake stitched shoes, less expensive than Goodyear welts.

Cons: Less flexible than Blake stitched shoes, not as well-constructed as Goodyear welted shoes.

The Welted Shoe

This type of shoe has a welt sewn to the upper and inner sole by hand to which the outer sole is stitched by hand as well with a heavily pitched thick linen thread. This type was the preferred one of the US Army and was preferred to pegged footwear.

Goodyear welted shoes are widely considered to be the best constructed around. It’s the oldest and most labor-intensive construction method in existence. It’s constructed in such a way that any cobbler can resole this shoe repeatedly and it’s incredibly durable. Usually made with double soles with outsoles that jut out from the upper, this construction method is widely utilized in British footwear in particular.