- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

Competition for patents in 19th century Belgium

The Belgian state was founded in 1830, and at that time the country was in the middle of an unprecedented industrial expansion. Technical innovation was a high priority for the state. Between 1830 and 1880, Belgium produced a number of patents per inhabitant that was the highest in the world . In the first part of his thesis Arnaud Péters discusses the Belgian patent system, and the national structure established for the recognition of intellectual property. How was the Belgian system designed? What were its features? How did it promote innovation?

The Belgian patent system

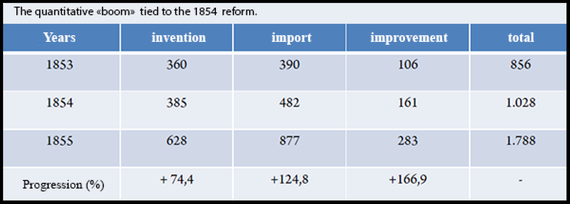

In the 19th century, the Belgians went crazy over patents. One explanation of this mania was the absence of any legal restriction on the declaration of a patent. In Belgium as in France all patents were recognized and accepted, which is not the case in all countries. In Germany or in the United States, f.e., patents that do not represent the interests of a local industry, or which do not include enough technical qualities were not accepted. On Belgian soil, the first complete legislation on patents was French, and dated from 1791. For the first time, rights to property were recognized on behalf of inventors, allowing them to hold a monopoly over the production of their invention for a period of 5, 10 or 15 years. This law provided for three kinds of patents. Firstly, a patent of invention conferred upon the inventor a monopoly on the use of an invention or process that was the creation of the patent holder's mind. Secondly, in a system in which patents had a national scope of recognition, a patent of importation allowed a patent recognized in one country to be transferred in another. Finally, an improvement patent was based on improvements to the substance of an existing patent. These categories of French origin continued to exist under William of Orange, who wrote a new law in 1817 which did not have to be materially altered until 1854. In 1854, several significant changes occurred. The failings of the patent law were becoming a problem, and it was apparent that the laws needed to be amended. The new law contained several new things. Patents were now recognized for a (maximum) period of 20 years. The process of obtaining a patent was opened up to more people, and progressivity of cost was introduced. The price of a patent, very low during the first years, increased considerably at the moment when it became profitable for the inventor. As in the past, no preliminary examination of the matter of a patent was provided for. At a time when industrialization was accelerating and the system was becoming more democratic, obtaining patents became very desirable. The statute of the "imported" patents was also adapted in order to reward the original patent holder more generously. Previously a foreign patent could be appropriated at will and "imported" to Belgium, even without the consent of the original patent holder. Now the law would make essential that consent. This change in the law caused quite a stir outside Belgium, and in fact the number of imported patents increased considerably after the legislative reform of 1854.

Different types of inventors and patent applicants

Arnaud Péters illustrates the first part of his research with the help of one main source: historical patent data. He was able to build and to query a database of all existing patents. Péters shows that in Belgium and outside it, the number of patents increased very sharply after 1854, and the ranks of inventors became a more diverse group. "Patents were claimed by independent people, industrial companies or business people," he says. "An investigation shows that individuals were often representatives of companies. At Vieille-Montagne, from 1853, patents were applied for in the name of the general director of the company. There were many individual persons who applied for patents, particularly those who were referred to as 'polyvalent and isolated inventors'. They patented things in many areas, and they were not representatives of a company, or the attachment was not a controlling one. And it was rare for their patents to be requested by industrial companies". Péters also shows that this increase in patenting activity was associated with the professionalization of two occupations - engineer and lawyer - that would be of tremendous importance in the history of patents and innovation. At a time when more and more people (and more and more different kinds of people) were seeking patents, the earliest engineering schools opened, including one at Liège. Once they obtained their diplomas, young engineers entered the patent game. At the same time the new profession of "patent agent" developed mainly among lawyers. These agents acted as intermediaries between Belgium and foreign countries on behalf of the holders of imported patents. Inspired by this new way of doing business, many lawyers began to apply for patents in their own names.

Patents and industrial innovation

The high number of patents per inhabitant and the spectacular boom occasioned by the 1854 reform are evidence of the competition over patentable innovations that took place during the 19th century in Belgium. At the same time Belgian industry was developing in an impressive way. Can we conclude that competition over patents was a factor in the growth of industry during the period? Did it foster growth? Or were the two phenomena independent?

Arnaud Péters gives several different answers to these questions. First, he points out that many patents were never developed in industrial applications, and most of them fell back into the public domain after two years. For some inventors, patents were an end in themselves. Many patents' technical value was never verified ; many of them were never put to a practical test. Corentin De Favereau, a Ph.D. in history at the Catholic University of Louvain who collaborated with Arnaud Péters, wrote a thesis on agricultural patents. His research shows the importance of advertising for patent applicants. During the 19th century, being able to call oneself an inventor with patents was a matter of prestige. "Some inventors applied for a patent just to to improve their reputation, but in fact in many cases their patents quickly expired and went back into the public domain because they didn't act on the rights granted, or because they failed to pay annual fees for the maintenance of the patents," said Arnaud Péters. And it was rare for anyone to be hauled into court for fake patents. There were only 104 such cases in court records for the period 1817-1873 - an insignificant number compared to the number of patents granted. These elements make it appear that the average economic value of a patent was very low, and that patents did not really contribute to technical innovation. This analysis is opposed to that of some economists, among whom is the British Douglass North. For North, industrial development in 18th and 19th century England is clearly the result of the patent system. His way of looking at the matter has been questioned among others by America's Petra Moser, for whom the relationship between patents and innovation is still rather tenuous during the 19th century. According to Moser, only in the 20th century did the relationship become more obvious.

The Vieille-Montagne patents

In focusing on the case study of the zinc industry, and most particularly on the history of the Vieille-Montagne company from 1837 to 1873, Arnaud Péters is trying to clarify the link between industrial innovation and patenting activity. He backs up his quantitative analysis with a technical analysis, made possible thanks to a documentation that is unusually rich; the archives of the company, "Mines et fonderies de zinc" of VieilleMontagne, the first multinational company in Europe and the most important company in the Belgian zinc industry. The archives altered the focus of Péters' research, by providing material for a case study. The archives allowed him to examine and study many patents, but also to get to know many actors in the national and international industrial system "The idea was not to be satisfied with the systematic approach, which is too general and which by itself does not allow us to understand the mechanism of innovation. Thus I have conducted an analysis of each patent that had anything to do with zinc, and then tried to understand how these patents were used and assigned worth in factories". In the zinc industry, the use of patents is symptomatic. The in-depth study of patents allowed Arnaud Péters to show that there are multiple uses for patents. As mentioned above, some patents are used as advertising. To hold a patent was a mark of prestige that benefited inventors, giving them a certain aura. This kind of use for a patent is not of great economic interest, and the patents involved rarely serve any important purpose in industry. Other patents have a strategic purpose. Vielle-Montagne was the source of many types of industrial pollution, and during the second half of the 19th century the authorities were putting pressure on the company to do something about it. In order to improve its public image, the company invested in research to try to find processes that produced less pollution. However, patents in this area were quickly abandoned. Although the pollution problems were still around, the company stopped investing in pollution control, apparently hoping the initial effort into industrial processes that might produce less pollution would be enough to improve the company's image. Patents also are part of what we could call indirect application: competitive situation analysis. From the 1840's and 1850's, Vieille-Montagne practiced an early form of technological monitoring. The directors of the factories regularly sent engineers to Brussels so they could read the patents applied for by their competitors. The company archives have documents referring to many of the inventions that appeared in the 19th century, which are commented on or criticized by these engineers. Thus, competitors' patents were a valuable form of research and a stimulus to inventors. This example appears to show that patents contribute to the process of invention, but the case of technological monitoring is still an exception with regard to that time period, and remains marginal. Patents that determine the direction of an industry are rare, but there are some examples of success. In the zinc industry, there were a half-dozen patents that had significant economic impact. These patents are called "monopolistic", and they allow the patent holder to enjoy a technological advantage. Whether the matter of a patent passed into general practice in an industry or was a simple failure, patents are still very interesting, in the opinion of Arnaud Péters: "The purpose of my research was not to give an account of important patents that appeared during the 19th century but to offer a holistic concept of innovation, that is, by describing failures as well as successes. The technical value of patents is very uncertain, but they all teach us something about industrial problems in the 19th century".