- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

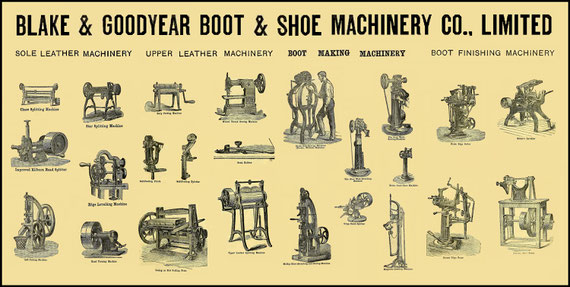

SHOE MAKING MACHINES

SHOE MACHINERY

by Frederick J. Allen

1916

The invention of shoe machinery, from about the middle of the last century, has revolutionized shoe manufacture. The story of the patient development of one machine after another, until the dexterity of the human fingers has been equalled, reads like a romance. Most of these machines have been invented by shoe workers themselves, often after long toil and study of particular processes. Inventive genius and mechanical skill have been granted about 7.000 patents on shoe machinery since the establishment of the United States Patent Office in 1836. Sometimes there have been a score or more on a single machine, to protect it as it has been built up part by part. New patents are constantly being granted, nineteen being announced in one week in November, 1914, during the preparation of this chapter. In making an ordinary shoe today there are one hundred and seventy-four machine operations, performed upon one hundred and fifty-four different machines and thirty-six hand operations, or altogether two hundred and ten processes. About three hundred different machines are used in the manufacture of all kinds of footwear and the number of processes is considerably increased.

Three Stages of Development

There are three conspicuous stages of development in the invention and use of shoe machinery.

The first stage is that of the upper-stitching machine, by which the top parts of the shoe are machine-sewed instead of being sewed by hand.

The second is that of the sole-sewing machine, by which the soles are attached to the uppers with a machine instead of by hand.

The third stage is that of machine-welting, in its modern form. This is an improved method of sewing on the sole, so that the shoe is flexible, as was the old hand-sewed shoe.

Other machines are subordinate to these in general importance and mark steps of advancement in minor processes and features of shoe manufacture. An account of the more important machines used in shoe manufacture is given herewith, in the order of their invention. As we shall meet these in operation in our study of factory departments, some knowledge of each machine will help our understanding of a process and of the running of the machine as an occupation.

The Wooden Peg (1815)

Heels were fastened to shoes by hand-made wooden pegs as early as the sixteenth century. Preceding the use of shoe machines came the machine-made peg in 1815. Up to that time the bottom of the shoe had been fastened to the upper by sewing with heavy thread or "waxed ends" and in the case of some heavy boots by copper nails. This sewing was a slow, hard process and was necessarily done by men. The invention of the shoe peg was a great gain. The first pegs were whittled out by hand in imitation of the nail. When pegs were properly driven, piercing both the outer and inner sole, with the upper leather well drawn in between the two, the result was a great improvement in strength and durability over the old method. But the pegged shoes were less flexible than the sewed shoe and many persons still asked for shoes made by the old method.

A pegging machine was invented in 1833, but none came into general or successful use until about 1857.

The pegging machine and the McKay machine revolutionized the industry, but did not put an end to hand shoemaking, which has continued to the present day, yet with a constantly diminishing importance. The great gain, of course, was the large increase in the number of shoes made, with a lowering of the retail price and a widening shoe market.

The Rolling Machine (1845)

The first machine to be widely used in shoemaking was the rolling machine for solidifying sole leather, which was introduced about 1845. Formerly the shoemaker was obliged to pound sole leather upon a lapstone with a flat-faced hammer, to make it firm and durable for the shoe bottom. This was a laborious process and sometimes took a half hour for what can be done between the strong rollers of the machine in one minute.

The Howe' Improved Patent Sewing Machine (1852)

In 1851 John Brooks Nichols saw the advertisement of a sewing machines published by I. M. Singer & Co., in a Boston news paper. He decided that the sewing machine would become of great value. So he bought one of the first lot of 25 machines that I. M. Singer & Co. made. At the time, the sewing machine had not been perfected for use in stitching leather. Mr. Nichols, a shoemaker by trade, naturally wondered why the machine couldn’t be made to stitch leather. He began to experiment, using scraps of kid leather that he brought from Lynn shoe factories. He found that his sewing machine wouldn’t stitch leather neatly because the needle was bigger than the thread. The seams were loose and the stitches coarse. He went to the needle manufacturers and got them to make needles of new shapes and sizes. These needles he filed and even smoothed down with emery paper to get them of the desired small size. He also went to the manufacturers of silk and cotton threads and got them to make new kinds of thread for his experiments. After months of patient labour, he succeeded in stitching leather on the machine so that its stitches compared favorably with the stitches of the shoe binders.

This machine was remodeled so that he was able to use it for stitching shoes. He sold to three Lynn manufacturers (Scudder Moore, John Wooldredge and Walter Keene), rights to use the machine for stitching leather in Essex County. Mr. Nichols became instructor of operators on the machines used by these firms. At this time Mr. Nichols first heard of Elias Howe. Howe was just home from his unhappy European trip and was laying claim to his patent rights. Mr. Nichols went to him in Cambridge and asked for permission to make use of his invention in stitching shoes. Mr. Howe replied that Mr. Nichols was the first man who had asked permission to use his invention. Asked why he did not take out a patent for his “invention”, he said: “There was no new principle disclosed in it. It was but an adaptation and rearrangement of known means for accomplishing the purpose”. He did not think it a proper subject for a patent and yet, since that time many hundreds of sewing machine patents have been granted that had but a fraction of the originality that appeared in this design which the modest author thought unworthy of the title of “invention”. There was, however, no occasion for a patent, as his relations with Howe and through Howe with the “Combination”, gave all the protection that any additional patents could have given.

extract from:

SHOE MAKING OLD and NEW by Fred A. Gannon

and

LIVING FATHERS OF THE TRADE by Sewing Machine Times

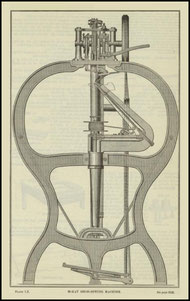

The McKay Shoe-Sewing Machine (1858)

In 1858, Mr. Lyman Reed Blake, a shoemaker of South Abington, now the town of Whitman, Massachusetts, patented a machine which sewed the soles of shoes to the uppers (US 20.775). This was improved in 1862, by Robert Mathies and manufactured by Gordon McKay, a capitalist and manufacturer. It became known as the McKay sewing machine (US 36.163). These machines were first used in the factory of William Porter & Sons of Lynn in 1861 or 1862 and were run by foot power. The McKay machine ushered in the second period of development in shoe machinery and has done more than any other to modernize shoe manufacture.

The Goodyear Welt Machine (1862-1876)

In 1862 Auguste Destouy, a New York mechanic, invented a machine with a curved needle for sewing turn shoes (US 34.413). This was later improved by as many as eight different mechanical experts employed by Charles Goodyear. The machine was afterwards adapted to the sewing of the welt in the bottom of the shoe, with patents in 1871 and 1875 and became the famous Goodyear welt machine. This marks the third great period of development in shoe machinery. McKay and Goodyear were not themselves originators; they adapted and promoted the inventions of shoe worker and mechanic. Other inventions no doubt lacked such promoters and were lost to the industry.

Edge-Trimming and Heel-Trimming Machines (1877)

Edge-trimming and heel-trimming machines were introduced about the year 1877 and soon played a very important part in shoe manufacture. Previous to the introduction of these machines hand trimmers, or "whittlers", as they were called, received very high wages, sometimes double those of lasters who were also highly paid. Considerable opposition was offered to the trimming machines, but their speed, uniformity of work and saving to the manufacturer made their adoption and universal use inevitable.

The Lasting Machine (1883)

Though several attempts had been made to invent and operate lasting machines, yet long after it was possible and profitable to sew shoes by machinery, it was still necessary to last them by hand. Shoe operatives in all lines opposed the introduction of machinery, feeling that it would reduce their numbers, shorten the period of employment each year and make them more dependent upon the manufacturer. Foremost in this opposition to machinery were the hand lasters. They were strongly organized and secured a very high wage, ranging from twenty to thirty dollars a week or more at a time when earnings on most processes were low as compared with present day wages in the shoe factory. The lasters boasted that their trade could never be taken away from them. Jan Ernst Matzeliger, a young man destined to accomplish what seemed impossible, came to Lynn from Dutch Guiana. He was the son of an engineer and himself an expert machinist. In a Lynn shoe factory he learned to operate a McKay machine and heard the boast of the hand lasters. Matzeliger began to work secretly on a model for a lasting machine. The first model was a failure, as was also a second. A third, however, was so satisfactory that money was advanced to the inventor for a fourth, in 1883. Matzeliger died while working upon this, but it was completed by other men and became the foundation of the modern consolidated lasting machine. The old lasters said that this machine sung to them as it worked, "I've got your job! I've got your job!" Some of the motions of the machine are like those of the hand and fingers, drawing the parts of the leather into place and fastening them by tacks. The hand worker lasted perhaps fifty pairs of shoes a day; the machine operator lasts from 300 to 700 pairs in a day of ten hours.

( see also: www.ct-williams.com/blog )

The Pulling- Over Machine

This improvement was introduced early in the present century. The pulling-over machine prepares the shoe for the lasting machine. It centers the upper upon the last, draws the sides and toe into place with pincers which work like fingers and temporarily fastens these parts with tacks for lasting. "It is the acme of shoe machinery intricacy and accuracy and years of study and over $1.000.000 were spent in its development".(*) While his amount seems large it probably means a saving to the shoe manufacturers of the United States of four times the amount each year.

(*)From A Primer of Boots and Shoes. The United Shoe Machinery Company.

Joseph L. Joyce

Joseph L. Joyce was a shoe manufacturer of New Haven, Connecticut and a friend of Goodyear and McKay. From 1860 to 1890 he obtained many patents which greatly improved shoe machinery and the art of manufacturing.

Power in Shoe Manufacture

Hand and foot power were first used for shoe making. In 1855 William F. Trowbridge, at Feltonville, Massachusetts, now a part of Marlboro, first applied horse power to shoe manufacture. Soon after this steam or waterpower was in use in all factories. In 1890 the electric motor was introduced and has gradually taken the place of the steam engine.

The Development of the Shoe Shank

As an indication of the development of a minor part of a shoe and of the simple machinery necessary for its manufacture and as an example of a subsidiary industry, the main facts in the growth of the shank industry are here presented. Primarily the shank is that part of the sole between the heel and the ball of a shoe. In shoemaking the shank is a reinforcement placed between the outer and inner soles of a shoe in that part extending from the heel to the ball of the foot. Its purpose is to give shape or style and elasticity to the shoe. Fifty years ago the hand shoemaker used hard scraps of leather for shoe shanks, trimmed to the desired shape. Thin pieces of wood, molded to shape on primitive machines, soon came into use and later strips of leather board. From 1877 to 1885 a single firm in this country had a monopoly of molded shanks. About 1885 numerous patents were granted on shanks and on machinery for producing them. One form was a strip of flexible steel with leatherboard cover or casing. All the kinds of shanks described are in use at the present time, according to the kind and grade of shoes to be manufactured. There is, however, a constant tendency to use shanks of the better quality, for shoes sell better and keep their shape better with the more durable shank reinforcement. The use of prepared shanks is universal and the world's supply is produced mainly in this country. There are machines large and small, simple and complicated, for making the various lesser parts of a shoe and its accessories, such as heels, counters, tips, eyelets, buckles, nails, thread, laces, polishing brushes and so on, as well as machines for manufacturing the various items of factory equipment.

Operating a Complicated Machine

In some factories it is necessary and in all factories advisable, that the operator of a modern, complicated shoe machine should understand its parts thoroughly and be able to make the adjustments and simple repairs that may be needed at any time. The worker who has mechanical ability may learn to adjust and repair his machine by actual experience in running it. The mechanically expert operative is able to keep the machine running to its full capacity and to lengthen its period of efficient wear. He is thus worth more to the factory and has increased earning power under the prevailing method of piece work.

The Leasing System

The leasing system of shoe machinery was introduced in 1861 by Gordon McKay, when it was found difficult to sell to manufacturers the Blake machine for sewing uppers and soles together. Such machines were costly and the capital of most shoe manufacturers was small at that time. The leasing system, on a royalty basis, enabled the manufacturers to have the advantage both of the machine and of unreduced capital for manufacture.

The Care of Machinery

Owing to the unusual conditions just described in the shoe industry and through the leasing of machinery, there was early developed by the machine manufacturing company a force of men who were trained in the care of machinery and located at convenient centers, so as to go wherever machinery trouble existed. With the evolution of the shoe machinery business and the various machines used in the bottoming of shoes under centralized control, relatively few factories maintain a force of special mechanics and these are generally for the purpose of millwrighting and construction. At the present time a large force of expert "roadmen", as they are called, is located in all the large shoe manufacturing centers and in these agencies or branch offices from which they travel there is constantly maintained an immediately available supply of the many machine parts which are liable to wear or breakage. These parts are all numbered and catalogued, so that as soon as a part breaks or a machine goes out of adjustment, a telephone message brings to the factory the required machine part. This service has been expanded to cover the instruction of operators upon the machines when set up in the factory.

The Standardization of Machinery

Because of standardization of machinery and processes and through co-operation between the manufacturer of shoe machinery and the shoe manufacturer, the growth of the industry during the last twenty years has surpassed all former periods. Today, manufacturers, large and small, can secure machinery by leasing it and nearly all factories are conducted entirely on this basis. This fact will make our study of the industry easier. We shall be studying operations on standard machines, used quite generally in this country and in many factories in other countries. We must remember, however, that improvements are constantly being made, that a process may be entirely changed on any day and that the most skillful operatives of machines are in constant demand throughout the country.

SHOE MACHINERY by Frederick J. Allen 1916

THE GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF MACHINERY

Methods of making shoes have been revolutionized by American shoemakers in the past 275 years. Changes have been made slowly. One generation improving upon the methods of its predecessors, until the sum total of the changes was a revolution of the industry from a manual to a mechanic industry. Shoes of colonial days were commonly sewed by hand. Heavy shoes were welt sewed and light shoes were turn made. Some heavy boots were copper nailed.

One of the first improvements in making shoes came from the use of the shoe peg. The historical sketch of the shoe industry, published in the U. S. census reports for 1900 is authority for the statement that the shoe peg was invented in 1815. The first pegs were whittled out by hand. The pegs, when properly driven, firmly fastened the sole to the uppers.

(*) The first machine in the shoe industry appears to have been a shoe pegging machine. It was invented by Samuel Preston, a Danvers, Massachusetts, shoe manufacturer, in 1833. A pair of shoes pegged on it is preserved in the Essex Institute, in Salem. The pegging machine, however did not come into successful use until about 1859, when a machine for pegging boots and shoes patented in October, 1851, (US 8.465) by A. C. Gallahue, was perfected. This machine really began the revolution of the shoe industry, from a manual to a mechanical industry.

Shoe Making Old and New

by Fred A. Gannon

1911

*********************************************************

(*)

The first large manufactory in which machinery was employed in the manufacture of boots and shoes was that established at Battersea, in England, by Brunel, the celebrated engineer, for the supply of shoes to the British army during the last war. The labor was performed by the Chelsea pensioners and the process employed was that of riveting the soles by double rows of small nails, the bottoms being at the same time thickly studded with copper or iron nails. The ingenious proprietor, who had a patent, contrived many other small machines for cutting out and hardening the leather by rolling, punching the holes, forming and inserting the nails, &c, some of which are still used in France. But the method appears to have fallen into disuse after the peace in 1815, probably on account of the cheapness of manual labor.

The manufacture of pegged boots and shoes, which now forms the greater proportion of the work of our factories and the greatest improvement yet made in the business, as far as labor is concerned, was practiced as early as 1812 in New York and very generally in Connecticut, although this valuable invention has been ascribed to Joseph Walker, of Hopkinton, Massachusetts, about the year 1818. We find that a patent for a method of pegging boots and shoes was taken out in July, 1811, by Samuel B. Hitchcock & John Bement, of Homer, New York and another by Robert U. Richards, of Norwalk, Connecticut, in May, 1812, for the use of wooden pegs, screws, &c. Samuel Milliken, of Lexington, Massachusetts, in 1807, took out a patent for metallic bottoms for boots and shoes.

A pegging machine was the subject of a patent by Nathan Leonard, of Merrimack, New Hampshire, in June, 1829. Other contrivances for the same purpose were brought forward at different times, among which may be mentioned the ingenious machine for pegging boots and shoes patented in 1851 by A. T. Gallahue, of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, where it was put in practical operation. It enabled one man to peg a boot or shoe with two rows of pegs on each side in three minutes, cutting its own pegs at the same time. In the following year patents were issued to Mr. Gallahue for a further improvement and to seven other different persons for shoe-pegging machines.

The pegging machines of Sturtevant(*) and of Tripps & Hill have proved useful inventions. Several minor inventions have materially contributed to the extension of the pegged shoe and boot manufacture, which now constitutes at least three-fourths of the general business.

US 9.629 Seth D. Tripp April 12, 1853

all US patent models prior to 1836 were lost in a Patent Office fire of that year

In 1851, Alpheus C. Gallahue, was of Matamoras, Washington, State of Ohio

Manufacturers of the United States 1860

Washington:

Government Printing Office 1865

*********************************************************

The McKay machine, which came soon after it, is given the credit of revolutionizing the industry. The first machine in successful practical use in the shoe industry was the rolling machine. It is a simple machine, consisting of two iron rollers. A shoemaker passed a pair of soles through the rollers and so compressed the leather. By using the rolling machine, the shoemaker saved himself half an hour labor of pounding a pair of soles on a lap stone with a flat face hammer. The McKay machine and the pegging machine were rapidly adopted by shoe manufacturers. But they did not put an end to the occupation of hand shoemaking. The McKay shoes and the pegged shoes, too, were stiff. Their soles were like a board. People were accustomed to the flexible hand sewed shoes, and those persons who could afford it continued to buy hand sewed shoes made by custom shoemakers.

In 1862 August Destroy secured patents on a welt sewing machine. He assigned his patents to James Hanan, of Hanan & Son, shoe manufacturers, of Brooklyn. Mr. Hanan interested Charles Goodyear, an expert machinist, in the machine. Mr. Goodyear developed it and the machine took his name, even as the invention of Blake took the name of McKay.

The welt sewing machine did not come into use until about 1876, however. From that time the industry of making shoes by hand began to wane rapidly. The machine accurately imitated hand methods of making shoes and sewed soles to uppers with stitches almost as fine as could the skilled hand shoemakers. There have been invented, developed and brought into use in the shoe industry a thousand and one machines besides these important and successful ones. All of them have contributed in a greater or less extent to the saving of time and increasing the wages of the shoemaker and to the improvement of product and decrease of price of product. These many machines, however, would have been of small value had they not been harnessed to the giant powers, steam and electricity. The first machines; were driven by hand power or foot power. Some enterprising shoe manufacturer adopted the horse mill that was in common use in the textile factories. In about 1855 the steam engine was substituted for the horse mill and along in 1890, the electric motor began to take the place of the, steam engine. William F. Trowbridge, an enterprising shoe manufacturer of Feltonville, now Trowbridge, Massachusetts, employed three stout Irishmen to turn over the main power wheel in his factory. Later, he employed his horse, ''Old General".

In 1855, Mr. Trowbridge had a steam engine set up in his factory. It was the first used in the shoemaking industry. One man performed the entire process of making shoes in colonial times. He did all his work with his own hands. Today, in some shops, a single shoe passes through the hands of 100 employees, 90 of whom operate machines. A colonial shoemaker spent a day, more or less making a pair of shoes. In one modem factory, a pair of fine shoes has been made in 15 minutes. There are few men today who can make a shoe, performing the entire operation. But there are some men who have built up organized establishments that will make twenty thousand pairs of shoes in a day.

Shoe Making Old and New

by Fred A. Gannon

1911

Shoes in the 1800's

As late as 1850 most shoes were made on absolutely straight lasts, there being no difference between the right and the left shoe. Breaking in a new pair of shoes was not easy. There were but two widths to a size; a basic last was used to produce what was known as a "slim" shoe. When it was necessary to make a "fat" or "stout" shoe the shoemaker placed over the cone of the last a pad of leather to create the additional foot room needed.

Up to 1850 all shoes were made with practically the same hand tools that were used in Egypt as early as the 14th century B.C. as a part of a sandal maker's equipment. To the curved awl, the chisel-like knife and the scraper, the shoemakers of the thirty-three intervening centuries had added only a few simple tools such as the pincers, the lapstone, the hammer and a variety of rubbing sticks used for finishing edges and heels.

Efforts had been made to develop machinery for shoe production. They had all failed and it remained for the shoemakers of the United States to create the first successful machinery for making shoes.

In 1845 the first machine to find a permanent place in the shoe industry came into use. It was the Rolling Machine, which replaced the lapstone and hammer previously used by hand shoemakers for pounding sole leather, a method of increasing wear by compacting the fibres. This was followed in 1846 by Elias Howe's invention of the sewing machine. The success of this major invention seems to have set up a chain reaction of research and development that has gone on ever since. Today there are no major operations left in shoemaking that are not done better by machinery than formerly by hand.

In 1858, Lyman R. Blake, a shoemaker, invented a machine for sewing the soles of shoes to the uppers. His patents were purchased by Gordon McKay, who improved upon Blake's invention. The shoes made on this machine came to be called "McKays". During the Civil War, many shoemakers were called into the armies, thereby creating a serious shortage of shoes for both soldiers and civilians. The introduction of the Mckay was speeded up in an effort to relieve the shortage.

Even when McKay had perfected the machines, he found it very difficult to sell them. He was on the point of giving up since he had spent all the money he could spare, when he thought of a new plan. He went back to the shoemakers who had laughed at the idea of making shoes by machinery, but who needed some means of increased production. He told them that he would put the machines in their factories, if they would pay him a small part of what the machine would save on each pair.

McKay issued "Royalty Stamps", representing the payments made on the machinemade shoes. This method of introducing machines became the accepted practice in the industry. Mention is made of it because it had two important bearings on the industry. First, shoe manufacturers were able to use machinery without tying up large sums of money. This meant that, in the event a new shoe style suddenly became popular and called for major changes in shoe construction methods and production equipment, the manufacturer wasn't left with a huge investment in machinery made obsolete by these changes, nor with the prospect of further investment for new machines. Second, it developed a type of service which has proven to be of great value in the shoe and other industries.

This unique service was used in the shoe industry long before it spread to other industries. McKay quickly found that in order to ensure payment for the use of the machines it was necessary to keep them in operation. A machine which wasn't working did not earn any money for Mckay. He therefore made parts interchangeable and organized and trained a group of experts who could be sent wherever machines needed replacement of parts or adjustment.

In 1875 a machine for making a different type of shoe was developed. Later known as the Goodyear Welt Sewing Machine, it was used for making both Welt and Turn shoes. These machines became successful under the management of Charles Goodyear jr., the son of the famous inventor of the process of vulcanizing rubber.

Following McKay's example, Goodyear's name became associated with the group of machinery which included the machines for sewing Welt an Turn shoes and a great many auxiliary machines which were developed for use in connection with them.

Invention as a product of continuous research has progressed at an almost incredible pace ever since. This has required great sums of money, sometimes more than a million dollars, to perfect one shoemaking machine and tireless patience and effort. Inventors have often mechanized hand operations that seemed impossible for any machine.

We have progressed along way from the lasting pincer, a simple combination of gripper and lever. For centuries it was the hand shoemaker's only tool for shaping the shoe around the form on which it is made, aided only by his thumbs and tacks, The lasting pincer is a good tool and is still occasionally useful; with it a century ago a man with great effort might form or last a few pair in a long day. Today's automatic toe laster for Goodyear Welt shoes can last 1.200 pairs in an 8-hour day.

taken from:

SHOE HISTORY