- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

ELIAS HOWE JR., INVENTOR OF

THE SEWING MACHINE

1819-1919

A CENTENNIAL ADDRESS

BORN IN A CRADLE OF INVENTION

The succession of master minds in a particular locality compels us to believe in the spiritual consanguinity of genius. It is an heredity much greater than that of blood. It is an heredity of spirit, that second birth that is not flesh-born but spirit-born. Especially do we need the transmission of its influence in America and in New England today. With such a reflex action upon us today of geniuses of yesterday, America celebrates the centennials of founders, authors and creators and with this motive, we celebrate the birth of the inventor of the sewing machine, Elias Howe, Jr., born in the hills of Spencer at the Commonwealth's heart, July 9, 1819, one hundred years ago. Though born but 27 years before, Howe patented, September 10, 1846, 73 years ago, the completed creation of his genius, a mechanism that revolutionized industry, the sewing machine, invented in Cambridge.

The New York Independent said not long ago that within the last 100 years no ten names could be assembled in one zone, greater than those of the ten master minds who sprang within a radius of ten miles of Worcester. Close upon us, in addition to that of Clara Barton, founder of the Red Cross, are the centenaries of two of these great internationally famous creators, born a century ago and within a few miles of one another. Within a month of the centenary of Elias Howe, occurred the centenary of William T. G. Morton of Charlton, discoverer of ether. Morton was also born on a Worcester County farm in 1819, the same year as Howe and in the same year, 1846, he patented his famous discovery. In the same years of like starvation and poverty from 1843 to 1846 that Howe worked up the steps to his invention, Morton worked up to his masterpiece of anaesthesia. These two Worcester County boy neighbors, thus each 27 at the climax of their creations, were each under twenty-five when their great ideas captured their vision at the same time.

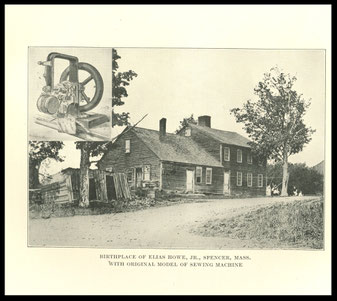

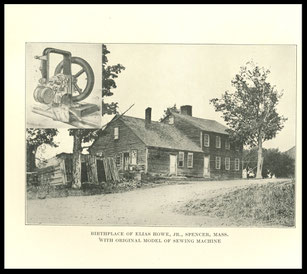

There are external ways of immortalizing that appeal to the eyegate of every passer-by, to every lad driving the cows home, and to every flashing auto. One is in "marked" birthplaces. The Howe Memorial Association has marked the birthplace of the Howe inventors, two miles out of Spencer, 15 feet back of two threshold stones that stand semi-exedra style, with doorstep base and slanting pillar indented in perpetuo with bronze plate. Here are the very steps trodden by the feet of the barefoot Howe boys. There were eight children in the family. Today the mill pond sings through the sluices across the road and rumbles through the broken iron gauges of the old mills. Three of these whirred their flanges there. Beside the old house, a perfect stone raceway allows the water to escape in a tempting, rippling trout brook that gurgles from back in the forest.

Already inventive streams had been strong in the family blood, blending three-fourths Bemis and one-fourth Howe. Captain Edward Bemis in 1745 commanded a Massachusetts company. When the French in retreat spiked their guns, on the inspiration of the moment he invented a way to drop out the spikes by heating and expanding the metal through building fires under them. In the home settlement, by the little dams and waterfalls challenging Yankee invention, machines for shoe pegs and other devices were long since made by the other members of the family. By the time the older Howe family in the late seventeen hundreds walked over those stone steps that now make the "markers", they were manufacturing grist and sawn lumber in three crude mills opposite the house. Here were made all of the simple essentials for bringing up a Puritan Yankee family, grist for bread and lumber for shelter and shingles and cider, perhaps over one-half of one per cent, a proportion not unknown to the earliest Puritans.

In the smaller wing of the old house, dating from the seventeen hundreds, were born Elias Howe, Jr.'s father's two brothers, William, the fifth son and Tyler, the fourth son. William was the inventor of the truss bridge. Unlike Elias, his nephew, it was later in life that William Howe had caught this fever for invention. He was then an inn keeper of a tavern standing till 1871, being a carpenter and builder also. In October, 1919, in an original letter from Richard Hawkins, a family connection at Springfield, came to me this authoritative sketch of him:

William Howe, who invented the celebrated Howe Truss Bridge in 1838 or 1839, was born in Spencer, Mass., May 12, 1803. He was a carpenter and builder and while erecting a church in Warren, Mass., which required a roof of some length, he conceived and built it under the system which has since been known as the Howe Truss. He afterwards built a bridge by the same system, about 60 feet long, in West Warren. At that time the Western Railroad was extended westerly from Springfield across the Connecticut River, a series of 7 spans of about 180 ft. each, single track.

He patented the bridge system in 1840 and it was once renewed. From that time to his death he had no other business but to sell rights to the patent. He received a large amount of money for its use by railroads and private parties, who bought all the state rights. As they were mostly his relatives, the business became a family affair.

The system was based on a combination of vertical rods of iron and vertical wood braces with top and bottom chords of timber. The plan was so easily figured for strain loads, and so safe and correct in principle, that the bridge became almost universal for railroads and towns and was largely used in foreign countries. Major-Gen. Whistler, who built the Western Railroad and afterwards built the railroad from Moscow to St. Petersburg, used the Howe Bridge in its construction. The Long Bridge, so-called (later taken down) at Washington, was of the same design.

There have never been any changes made in the original design except that the angle block formerly made of wood was changed to iron by Mr. Howe.

The bridge or truss system continues to be used in roof trusses and small spans, but the modern loads are so much increased that it has become impracticable to use the combination of the wood and iron, and iron bridges have become necessary for work of any magnitude.

Mr. Howe's residence after his invention was in Springfield, Mass. Tyler Howe, his brother (1800-1880), who had gone in a Pacific Ocean boat upon a disappointed quest for gold in California, hit upon the idea of a spring bed to take the place of the rigid berths in which he had been tossed about while on the vessel. He showed it to A. G. Pear of Cambridge in San Francisco in 1853. Then in 1855 he patented the elliptical spring bed and opened a successful factory in Cambridge. His house is still standing back of those old mill sites of his father near Spencer.

In 1819 Elias Howe, Jr., was born in the larger wing of the birthplace. By the time he was six he joined the older children in sticking wire teeth into strips of leather for carding cotton. Making easier the monotonous drudgery, there was a genius in the place architectonic with invention. The buzz of mill wheels filled the air in which Elias became acquainted with the elements of machinery, so far as known, and with machine tools. He absorbed an atmosphere kinetic with ingenuity. In 1866 he told James Parton that he was of the opinion that this early experience gave his mind its bent.

After five years of this struggle, as early as eleven, his Spartan father "bound him out "in 1830 to a neighboring farmer till the time of his apprenticeship should be over and he could return wearing his "freedom suit." But he was inclined to lameness from his birth, and he returned at twelve to stay home till sixteen.

The biographer, James Parton, who knew Howe so well, describes him, while congenitally lame, as a regular boy, curly headed, though a bit undersized, fond of jokes, and not over able or over fond of grinding from candle light to candle light on a hard-scrabble farm. Later he must have outgrown some of these traits, as his daughter, Jane R. Caldwell, wrote to me from New York, September 28, 1909, as to Parton's descriptions as follows: "My family and I are far from satisfied with the impressions given of my father's early life and character, which was full of purpose." However, Parton was right in his general psychoanalysis of his friend. Each of these characteristics could be true, one of the natural fun-loving human boy, the other of the controlled man chastened by suffering and responsibility and struggle. One would think more of him because he was no abnormal, mechanical crank, but thoroughly human.

In 1835, four years after his return home, he drifted to Lowell where he had heard of the vast cotton machine shops. But the sixteen-year-old mill hand lost his place in the panic of 1837. Then the "bobbin boy," N. P. Banks, his cousin, and later governor, Speaker of the House and Civil War general, took Elias' arm and drew him to Cambridge to a hemp-carding machine shop of a Professor Treadwell. The two boys in greasy jumpers and overalls worked side by side and roomed together.

At this critical age of awakening, no doubt Banks's aspirations could not but have been creative of ambition in Elias. From this time too, William Howe, the landlord of the sleepy tavern, who awakened just before 1840 to his inventive dreams of bridging the streams of the world and carrying railways on his spans through Europe, must also have stirred the imagination of Elias.

THE VISION OF A SEWING MACHINE

At 18, late in 1837, Elias Howe as journeyman entered a machine shop at 11 Cornhill, Boston, kept by Daniel Davis. Howe's employer manufactured optical instruments and was noted as a skilled repairer of intricate mechanical inventions. Elias himself made little improvements and worked at a bench and lathe, often hearing snatches of conversations of inventors who came in to talk over their half-finished machines.

After three years at the machine shop, in 1840, he was only getting $9.00 a week. But he married, on this salary of a dollar and a quarter a day. To support the wife and the family of three children coming on, one after another, put the boy husband under pressure. It almost crushed him. After work he was hardly able to get up from the bed upon which he threw himself supperless and worn, only wishing, as he told James Parton afterward, "to lie there forever and ever." In 1842, when Howe was now twenty-three years old, and had been in the shop five years, there came in an inventor of a little knitting machine that would not work. With the inventor was a promoter of the machine, the man who was his financial backer. Mr. Asa Davis, brother of Daniel, explained his plans were not complete, but he would make the model when perfected.

"Why don't you make a sewing machine?" asked Asa Davis, dissuading the man from wasting his time on a knitting machine.

"It can't be done," snapped the financial backer.

"Yes, it can. The man that can make a machine that will sew, will earn his everlasting fortune."

When Howe went home to Cambridge that night, his untapped reservoirs of inventive energy were pierced. No longer dormant from exhaustion, he mused upon the declared impossible invention. He could not dismiss the challenge from his awakened mind till his ingenuity grasped at an idea. "Thomas," he exclaimed the next morning to his fellow journeyman mechanic at the next bench and lathe, "I have gotten an idea of a sewing machine!".

In the meantime Howe's wife took in sewing to eke out. Lying supperless in bed after the exhausting day's work, his eye saved him from dropping off by following the motion of her arm. He was trying to discover a way to imitate it in an arm of wood and steel. What he would save if he could! He often imitated Mrs. Howe's arm movements. The mania of invention seized him deeper and deeper and would not let him rest. Thence, day and night, he aimed to materialize the ideas burrowing in his inventive imagination. Then in 1843 he set to work to make a machine to take the place of the human hand. Night after night he whittled upon models till morning. Nothing but piles of whittlings were the result. It would not work.

THE CRISIS OF THE INVENTION — THE NEEDLE WITH AN EYE AT THE POINT

He was halted at the needle's eye. Should it be a needle pointed at both ends with the eye in the middle, working up and down, thrusting the thread through each time? Through many nights of experiment he tried it. No — it would not work! Then why not another stitch using two threads, a shuttle and a curved needle? But where pierce the eye in the needle? Why not try it at the front end?

He cut coils of wire. He grooved them on one side with a pair of steel dies. He left in the middle a raised edge. With highly tempered steel at the needle's end, he drilled an eye. Then he inserted it in the crude whittled model. His contemporary, Parton, describes the moment thus: "One day in 1844, the thought flashed upon him — is it necessary that a machine should imitate the performance of the hand? May there not be another stitch? Here came the crisis of the invention, because the idea of using two threads, and forming a stitch by the aid of a shuttle and a curved needle with the eye near the point soon occurred to him. He felt that he had invented a sewing machine. It was in the month of October, 1844, that he was able to convince himself, by a rough model of wood and wire, that such a machine as he had projected, would sew."

The miracle of the sewing machine was achieved!

There is a remarkable letter which I have discovered from the living eyewitness and coworker on the original model. It is one that catches the invention at its birth from the worker at Howe's elbow on the next lathe at the very hour of invention. It has lain in the hands of Dr. Alonzo Bemis of Spencer. It is as follows:

Dec. 8, 1910.

Madisonville, Ohio.

Dr. Alonzo A. Bemis.

Dear Sir:

Probably I am the only man living who was with Howe when he invented it (the sewing machine) and worked on the model. In the year 1839, I went to work for Daniel Davis, philosophical instrument maker, at No. 11 Cornhill, Boston, Mass. Mr. Davis was the father of Daniel Davis, of Princeton. Elias Howe was then working for Mr. Davis as a journeyman. His bench, and lathe, was next to mine. Mr. Davis' shop was headquarters for all kinds of geniuses, inventors, etc. One day there came a man into the shop who wanted Davis to make a knitting machine. Mr. Asa Davis, brother of Mr. Daniel Davis, talked the plans over and said to the man: "Your plans are not complete. Perfect your invention and I will make the model." Asa remarked that if anybody could make a good, practical sewing machine a woman could use, there would be a fortune in it. That remark stuck in Elias' head. The next morning, he said to me, " Thomas, I have gotten an idea of a sewing machine."

Howe did not rest until he perfected the machine. He made a very coarse model but in that model was the embryo of all the sewing machines made to this day, and that was, pushing the eye of the needle through the cloth, instead of the point. In my leisure moments, I would work the machine with Howe. Everybody discouraged him. We found great trouble in passing a thread through the loop so as to lock the thread. When he conceived the idea of a shuttle, the sewing machine was practical.

Yours respectfully,

THOMAS HALL (85 yrs. old)

"I should like," adds Dr. Alonzo Bemis, "to correct an error which has found its way into the press on many occasions — that is: that the idea of the needle came to Elias Howe in a dream. This is not true. Mr. Howe was too much of a Yankee to place any dependence in dreams and the needle idea was worked out by careful thought and countless experiments."

After working upon the model, assisted sometimes by his fellow-mechanic, Thomas Hall, who tells us of it so interestingly, Howe found the increasing toil and increasing family and increasing expense upon the model too overwhelming a burden. With no money at hand to develop his invention, he turned to his father.

Elias Howe, Sr., had by this time left Spencer and moved to Cambridge. The inventive ingenuity of Tyler Howe, the one of his brothers who later invented the spring bed, had invented a system of cutting Palm Beach leaf for hat manufacture. Elias Howe, Jr.'s father, came to conduct the factory. This factory was at 740 Main St., Cambridge, below Lafayette Square. This "incubator of invention" is still standing, a plain three-story brick affair. It was then called the Palm Beach Hat Factory, later Howe's Spring Bed Factory. It has been a very nest of genius. Here the three Howes carried into materialization their developing dreams of the truss bridge, the spring bed, and the sewing machine. Here at times Morse worked on the telegraph, and Elias Howe made batteries and magnets at $1.25 a day. Here Graham Bell, after 1872, struggled with the invention of the telephone; and here John McTammany, who was working on the voting machine and the pneumatic tabulating system, disclosed his vision to invent a player piano, and with the inventor's urge came from the Howes' home at Spencer and worked it out.

Into his father's house in Cambridge in November, 1844, Elias Howe, Jr., removed his family and put his lathe and few machinist's tools into the garret, where he worked desperately hard, concentrating himself upon the model, yet rough and coarse. For the design must be made, he knew, into "iron and steel with the finish of a clock." At this time the Palm Beach factory burned out, and Elias Howe, Jr., with an invention in his head ready to revolutionize the world's industry, was blocked.

Here crops up an old Spencer friend, George Fisher. He was a schoolmate. Now he was a small coal and wood dealer in Cambridge. But in December, 1844, Fisher asked Howe with his family into his own house, and let him put his lathe under the slanting eaves in the garret. Besides, he loaned his old Spencer schoolmate $500 for which he would receive one half interest in the patent, if successful. He was one of the unknown soldiers of invention, the romance of whose chivalry was equal to that of the Yale friend who financed, and at the cost of his life saved, Eli Whitney. "I was the only one of his neighbors and friends in Cambridge that had any confidence in the success of the invention," Fisher declared. "Howe was generally looked upon as very visionary in undertaking anything of the kind and I was thought very foolish in assisting him."

To this centennial celebration, October, 1919 — to this house on Brattle Street where Worcester wrote the Dictionary —has come a lady, the daughter of this chivalrous friend, to confirm the facts of his friendship.(1)

Winter passed. But here by April, 1845, the steel model grew into form. The needle shot through the cloth, sewing a perfect seam. By May it was complete, and in July he sewed two suits of clothes.

(1). Mrs. Austin C. Wellington (Sarah Cordelia Fisher).

THE VICTORY OVER LABOR MOBS

Starvation near his door and the $500 of George Fisher exhausted, Howe could now manufacture his machine for sale, if it would sell. To do this, he asked a practical Boston tailor to Cambridge to test it by sewing. All at once the whole company of tailors in Boston rose up against the labor-saving device, crying out, "It will make us beggars by doing away with hand sewing!". For ten years they opposed Howe fiercely.

Howe would not be intimidated. He did not flinch. He would test the sewing machine before the world. He arranged to have a two

weeks' daily demonstration by himself at Quincy Hall Clothing Factory, sewing 250 stitches a minute and beating five of the fastest seamstresses, each doing a seam while he did five of the equal length, faster, neater and stronger. But as a result of violent opposition and the cost of the machine to manufacture, not a machine was ordered!

In the spring of 1846, starvation again stared him in the face, and frail and worn, he tried his hand as engineer at the throttle of a locomotive. But health failed him and he broke under the strain. He tried desperately to sell the model. To testify to this, an original eyewitness is at hand. It is Luther Stephenson of Hingham Center. His letter reads:

Hingham Center, Mass.

Oct. 7, 1910

Chairman of the Board of Selectmen,

Spencer, Mass. Dear Sir:

About the year 1846, I was employed in the store of Stephenson, Howard and Davis at No. 72 Water Street, Boston, the head of the firm being my father. I remember one afternoon Mr. Howe came to the store, bringing a model of his sewing machine for the inspection of the firm with the view of enlisting them in the manufacture of the same. The model was smaller than the machine now in use and was operated by a crank instead of a treadle as at the present time. This machine Mr. Howe brought as his own invention, and as original with him.

No arrangement was made with him by the firm for manufacturing the machine for business reasons.

Yours truly,

LUTHER STEPHENSON

Yet in his effort to introduce his machine, in his fight with the blindness of labor agitators, Howe won where other would-be inventors of the sewing machine failed because of exactly this same blind opposition to labor-saving machinery. This crushed Thomas Saint upon the eve of his success in England in 1790. This crushed Thimonnier of St. Etienne, France, upon the eve of his discovery in 1830.

In 1790, Thomas Saint patented a machine for sewing leather with a threaded awl with a hole in the point. A mob of glove makers, blindly enraged against this labor-saving machine, scrapped and smashed it.

Thimonnier in 1830 made eighty machines for stitching gloves, a sewing machine all but the feed. Thimonnier's needle, hooked at the end, descended through the cloth. It brought up the loop through a previously made loop and formed a chain in the upper surface of the fabric. A furious mob attacked his machines just as the government gave him war orders for his eighty models. Thimonnier they nearly murdered. In 1845 he patented it. He tried again in 1848, but the Revolution wrecked his plans. In 1851 he tried in London before the exposition. No notice was taken of his machine and he went home to France to die in the poorhouse in 1857.

In 1832, Walter Hunt in New York, in an alley in Abingdon Square, worked to invent a sewing machine and hit upon the shuttle to form the stitch. But it would not sew, and discouraged, he threw it into the rubbish heap in a garret on Gold Street.

What was it in Elias Howe that would not allow him to be crushed like Saint, Thimonnier and Hunt? It was Spencer's New England fighting blood and individual worth ingrained after generations from the blood of the sires. His was a victory over a phase of labor agitation that sought to own the laborer and kill the invention of his brain.

Howe met this crisis. All the hoots of labor mobs in the world could not floor him. He did not quail. He owned himself. They could not own him. Labor's contention today is, the laborer must own himself. It is not only capital that endangers self-ownership. There are kinds of labor agitation that would deny the mechanic's owning himself. And whenever this happens, labor just as much as capital should not be feared but conquered, and Howe conquered. Challenged at this crisis of labor, son of Spencer, he owned himself. Had he not, as with the others, he would have failed to invent the sewing machine.

Many also derided the invention as a folly. They never thought it would sew. This one thing prevented mob violence by the tailors against Howe. We all know Langley's airplane models of 1896, 1898 and 1903 lay in a Washington museum. They never flew because Langley was crushed by people laughing at him. Yet Glenn Curtis with some changes flew them over Washington.

Elias Howe's manhood was such that to none of these three things did he yield, mob violence, hardship or laughter. This stands as his greatest tribute, for it marks the man as well as the inventor.

THE BATTLE WITH CAPITAL AND INFRINGEMENT

In the midst of these rebuffs of fortune, Howe for four months buried himself again at work in Fisher's attic in Cambridge, and he made another machine. It was a model design, which he carried to Washington, where September 10, 1846, seventy-three years ago, it was approved and patented. But Washington people, when he exhibited it at a great fair, laughed at it as only a mechanical toy.

Fisher had now spent $2.000 and declares, "I had lost all confidence in the machine's paying anything." With nowhere else to go but the curb, Elias went back to his father's house with his family. In October he induced his father to send Amasa Howe across the Atlantic to England.

William Thomas of Cheapside was a somewhat chesty manufacturer employing 500 persons at making corsets, umbrellas, valises, shoes, etc. Amasa Howe offered him the machine. It did not take him long to decide. Thomas saw it was the crude beginning of a vast enterprise. For 250 pounds, $1.250, Amasa guilelessly sold him the machine and the right to use all he wanted and to patent it in England, paying three pounds royalty. He never paid at all. Thomas made a million dollars by 1867, for he had induced Amasa to beguile Elias across the sea in order to adapt the machine to corsets. February 5, 1847, Elias, pressed financially, sailed for England, to be joined by his wife and three children, whose passage Thomas paid.

As we behold the flying arm of steel in the sewing machine, we can never forget that, carbonized into it, is not only the genius of the inventor, but the sacrifice of a suffering woman, Howe's loyal wife. In eight months, at only ten dollars a week, Howe made the adaptation of this machine to corsets. At this point, having got out of him all he wanted, Thomas degraded Howe to petty repairs, the beginning of the end. At this snubbing by the English snob, the American of Spencer forebears arose hot in Howe's veins and he said, "I am poor, but will not kneel to one who treads your soil".

The selling of an inventor's brain to capital which alone can thenceforth own the rights is a pawning of the laborer, wrong then and wrong now. I mean by this, the signing over forever of the invention the laborer may make. It keeps him from owning himself and his brain. But the injustice of the capitalist could not crush Howe any more than the injustice of labor. He kowtowed neither to the mob nor the snob.Comes now another piece of human clay who had a spark in the clod, Charles Inglis, a coach maker. As in George Fisher, Howe in him found human kindness. With his family in three small rooms furnished by Inglis, he proceeded to construct his fourth machine. He was driven to the wall again. Then, forced by starvation and creditors to move into one little room in the cheapest quarters of Surrey, he decided to embark his wife and children for America. There were three children, two daughters and one son.

Inglis recalled: "Before his wife left London he had frequently borrowed money from me in sums of five pounds and requested me to get him credit for provisions. On the evening of Mrs. Howe's departure, the night was very wet and stormy and, her health being delicate, she was unable to walk. He had no money to pay the cab hire and he borrowed a few shillings from me to pay it, which he repaid by pledging some of his clothing. Some linen came home from his washerwoman for his wife and children on the day of her departure. She could not take it with her on account of not having money to pay this woman. Unable to get a wagon, Howe got a wheelbarrow to carry her trunks to the boat."

The acid of poverty ate in even more keenly after this. "He borrowed a shilling from me for the purpose of buying beans which I saw him cook and eat in his own room", added Inglis.

In four months more of the biting ignominy, Howe completed the machine, valued at $250. He could only get $25 for it in a note discounted at $20. Early in April, 1849, without enough to get home, he pawned the model of his first machine and the patent itself. Pushing his handcart of effects to the boat, he sought a job as cook in the steerage for emigrants. So he returned. Landing here four years after his first machine was made, he had but fifty cents in his pocket as reward. Hardly had he rented a cheap immigrant tenement, before he received the tidings that his wife, as a result of her faithful sufferings by his side in his struggle, was dying of consumption in Cambridge. With no means to get there, he waited for ten dollars from his father before he could reach her. He had to borrow a suit of clothes for the funeral. Downcast, bent, but not broken, he went home from the funeral to learn that the ship containing all his tools and effects had been wrecked at Cape Cod!

All was wrecked, but himself and his unconquerable soul.

Thus reduced in America as in England it would seem as if capital had crushed him as well as labor. In his absence, notwithstanding his original model and the elemental devices he had patented, manufacturing machinists were copying his machines everywhere. With it as a basis, inventors were making machines with their own designs added, but all using at least his chief original device, the needle with the eye in the end.

How could he contest? His model was three thousand miles away in a Surrey pawn shop. Hon. Anson Burlingame, however, acting as his representative, with a hundred dollars Howe raised, redeemed his precious model from "the three balls" in the neighborhood of England's hell of London paupers.

At home, however, four leading manufacturers were infringing upon his patent.

Elias Howe's father, who had loyally sheltered his boy again and again, sprang to his aid. He mortgaged his old Spencer farm in order to have funds to win the fight. George Bliss took Fisher's one half share and advanced the money for the patent war. Rufus Choate was Howe's famous attorney. He began the patent cases in United States courts that in time involved over 30.000 pages. Choate was to win.

In 1850, in New York, Elias Howe was constructing fourteen machines at a little one-horse Gold Street shop, the very street where Hunt had cast discarded his model of a sewing machine. In time, Isaac Merritt Singer, an actor and theatre manager in New York, saw Howe's machine. At work on a carving machine himself, he took it to Boston and while there repaired a number of sewing machines on which he made, as he declared, three devices as improvements. He at once began commercializing the machines and advertising. He invented, not the machine, but the sewing machine agent. This proved him the greatest commercial organizer for the sale of machines in the world. He did much to domesticate the machine and bring down its price. Yet he was not the inventor, and suddenly Elias Howe accused him of infringing upon his patent, No. 5.346 (US 4.750 ?). Singer contested it. Unable to prove an original model from England, France and China, he sought an earlier invention to at least supersede Howe's. He at last landed upon Hunt's machine of 1832 lying in a garret. He found Hunt, too, but Hunt could not make it run.

Everywhere Howe's patent held, in the uniform finding of the courts. In 1854 Judge Sprague of the Massachusetts Supreme Court decided "the plaintiff's patent valid and the defendant's machine an infringement." The court concluded, "There is no evidence in this case that leaves a shadow of doubt that for all the benefits conferred upon the public by the introduction of a sewing machine, the public are indebted to Elias Howe".

This is not saying that in 1849 and 1859, Allen B. Wilson did not construct a four-motion feed for a machine with an original device, later combined with Mr. Wheeler's rotating hook and shuttle and four-motion feed, the "Wheeler & Wilson" machine. And it is not saying that Gibbs, a Virginian farmer, did not make a great invention, a machine with a revolving hook, later the "Wilcox & Gibbs". Still other firms made improvements. Over one thousand improvements have been invented.

Yet the original device stood. Howe's claim was in brief: "I claim the use of an eye pointed needle, operating in connection with a shuttle looper, loop holder, or any other device by which one thread is passed through the loop of another and a stitch is thereby secured." As to his claims, the U. S. legal conclusion awarded him "vital points far-reaching, the foundation of the whole vast machine structure for sixty years".

The sewing machine battle ended with the other great firms paying a royalty to Howe of so much a machine. Then in 1856 they combined into a joint stock company or combination to prevent further losses by lawsuits and destructive legal battles. By 1860, just before the Civil War, fifteen years after Howe's first model which he could not get one order for, there were made 116,330 machines. By 1866, there were 750,000. By 1867 the country was making a thousand machines a day. Four thousand dollars a day was passing into Howe's hands in royalties when the Civil War broke.

Beyond all financial gain, Elias Howe had made incomputable gifts to his country. In creating domestic industry and in the emancipation of woman, the sewing machine transferred labor from sewing in homes to the factory system. It founded the shoe industry. It gave millions of women work. It emancipated millions of others from painful stitching.

It is not linen you're wearing out

But human creatures' lives.

Hood thus sang and when we count the stitches in one shirt we see it is so. For in each shirt there are over 20.000 stitches.

THE CIVIL WAR AND THE SUPREME SACRIFICE

Happily the touch of comedy had come into the tragedy. With undreamed-of wealth from royalties, Howe remarried. His wife was an English woman he had met in his travels — one perhaps who was a friend in need in bitter days. He established an estate at Bridgeport, next to P. T. Barnum's estate, and the two were neighbors and friends. Children that romped about this estate have been present at the 1919 centennial and record this phase of his life as a return on his part to the sunniness of his boyhood, a disposition from which he was never embittered and to which therefore he could return along the line of least resistance. There comes down to us today a gold tea-set bought at this time by Elias Howe and given to his father at his golden wedding. His picture at this stage with the fashionable mustachios and loud waistcoat of English pattern reveals a touch of the comedy and interlude in the tragedy, a bit of playtime in the afterglow. Unfortunately, in this picture, however, the interesting marks of struggle were creamed over with fuller face and figure. At this, for a moment, one fails to rejoice, for he misses the illumination born of struggle; for the great text is true, "Ye shall be illuminated, after a great fight of afflictions." An hour of re-illumination was now however to come, and "a great fight of afflictions".

It was the crisis of the Civil War.

Isaac Merrit Singer was said to be astonishing New York and London with his equipages and luxuries costing millions of dollars. Why should not Howe? War profits could be enormous. So far as doing for his country, did not his machines by rapid equipment put a million men in the field? Millions of further equipment had to be sewed, underclothes, blankets, overcoats, shoes, knapsacks, haversacks, cartridge belts, tents, balloons, harness, sails, bunting, hammocks. Was not inventing means to equip a million men with these millions of articles enough? The output of that machine reached, as we have seen, many millions of value by 1863, and 52,219 machines were used in war work alone. Sewing machines made even forts, for they made hundreds of thousands of bags to be filled with sand for their parapets. "One day," declared Parton, "during the war, at three o'clock in the afternoon an order from the War Department reached New York, by telegraph, for fifty thousand sandbags such as are needed in field works. By two o'clock the next afternoon the bags had been made and packed and shipped and started southward". In all, nineteen million dollars were saved to the country by the machines.

Was it not enough? Should Howe not have a good time like Singer, on his $4.000 a day and "play around" on his estate next P. T. Barnum's? But it was not enough for Howe. He had sacrificed his home, wife, health, sleep and food during sixteen years of suffering. Yet fourteen Bemises had been in the Revolution, eight in the Federal Army. The blood of his patriot fathers would not let him sit at ease, be a profiteer, and spend his $4.000 a day. Clara Barton's "What is money without a country?" was also his grand protestation. He would give all on the altar.

He could have been exempted, not only for age and on account of producing equipment, but because of his tendency to lameness. All of his life he hid it. Concealing it again, he enlisted as a private in the Seventh Regiment Infantry, Co. D, and was not to be mustered out till July, 1865. All through life's crushing pain, he never had complained. Why now? In an original letter to me from Jane R. Caldwell, once the little daughter, she says, "I have never heard him complain in all the tribulations of his sad home. Regarding my father's lameness, though it might have troubled him at times, I never heard him complain of it and doubt that except in the event of a long march he was disqualified as a soldier. He was a man of peace, but his patriotism was great and he was willing to serve his country to the extent of his ability".

He therefore gave his own body as a humble private. He did this though he raised and equipped the regiment. Though walking himself, he presented every officer a horse. When the company had not been paid for months, Howe stopped out of the disappointed files and asked the subordinate, "What is the back pay? When is it ready?" "When the Government is ready and not before," snapped the petty paymaster. "How much is due them?" "Thirty-one thousand dollars." Howe amazed the petty officer by seizing a pen and writing a check for the whole. Then he stepped up at his own time in the file of "buck" privates and received his back pay, $28.60.

Officially, he came out with no more honor than when he went in. Really, he came out with the greatest honor mankind can bestow, the record of a Christ-like self-bestowal and death for the cause. For in 1867, though twice a millionaire, as a victim of his terrific exertion, he died of Bright's disease in Brooklyn, N. Y.

Two years after his death, in 1869, at an International Exposition, great-souled France, though its Thimonnier failed at the point of success, at the hand of Emperor Louis, accorded Howe France's highest honor, the Cross of the Legion of Honor. At the fourth election, America, through the Committee of National Judges, elected Howe to the Hall of Fame, together with Daniel Boone and five others, the list ending with Rufus Choate, his patent attorney, who won his great cases on the patent which mark the triumph which we celebrate today — the triumph of the sewing machine.

In connection with the above paper, various portraits, documents, early models, etc., were exhibited.1 MRS. JOHN AMEE, a niece of Elias Howe, read some family letters. DR. ALONZO BEMIS of Spencer, the birthplace of Howe, spoke briefly. Among the members present was Mrs. Sarah Cordelia (Fisher) Wellington, daughter of George Fisher, in whose house at Cambridge the sewing machine was invented.

Mrs. Gozzaldi presented from Mrs. William B. Lambert a collection of papers on Cambridge history formerly belonging to the late John Reed, a member of the Society.

Voted that Mrs. Lambert's gift be accepted with thanks.

The meeting then adjourned.

A three-quarter length portrait of Howe, painted a year or two before his death, was loaned to the Society in 1914 by his grandson, Elias Howe Stockwell. By an arrangement with the Cambridge Public Library, it is at present hung on exhibition there. (See these Proceedings, ix, 61, 82.)

Howe's finished model of the sewing machine is in the Smithsonian Institution at Washington, but the Society has one of the earlier rough models in its collection.

source:

Cambridge Historical Society

Author: Percy H. Epler

(from page 122 to 139)

see also:

As reproduction of Historical artifacts, this works may contain errors of spelling and/or missing words and/or missing pages, poor pictures, etc.