- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

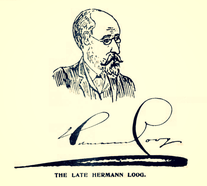

HERMANN LOOG

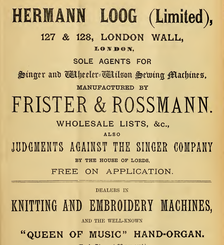

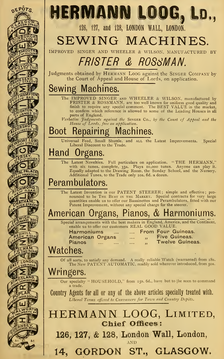

Hermann Loog was born in Germany in 1845 and after a first class education was articled for four years to a Jewish banker in Berlin and when about twenty years old came to England (1865) and entered a mercantile office as foreign correspondence clerk. By this time he had almost mastered three languages besides his mother tongue. Eight years later (1873) Hermann Loog starts in business for himself in London as a wholesale hatter (Gresham St. of the City of London) and in 1876 he contrives to obtain the wholesale agency for the United Kingdom for Frister & Rossmann's machines, which was previously owned by Isidor Nasch. Within a very short space of time hats were relegated to the background, Loog becoming severely smitten with that love for the sewing machine which has caused the undoing of some and yet has given to others a substantial competence. A this time Singers were still at war with other makers over the question of trade name and Hermann Loog, who was ever a fighter, could not do other than take a hand in the contest. accordingly he used the word Singer to describe one of the machines made by Frister and Rossmann in Berlin. A lawsuit followed and after total defeat in one Court, then a partial win, he succeeds in the House of Lords, but as there are retreats in war which are really victories, so there are wins in law courts which are fraught with such consequences as in the long run to be worse than a defeat. From this time forward Hermann Loog could never get rid of the idea that he had done a great work, he had beaten the Singer Company, as a far greater man than he, Newton Wilson, had failed to do. It is strange, however, that he could never realised exactly what he had achieved, which was merely this: He had used the name "Singer" as a descriptive term to a man in the trade who knew that the word was merely descriptive and he was not and could not be deceived. Newton Wilson, on the other hand, wanted to use the word "Singer" in transactions with the public, which the Courts could never be brought to permit. Poor Newton Wilson died a poor man at peace with his Maker as the result of unsuccessful litigation with Singers and Loog three years later follows him to the grave with a self inflicted bullet wound as the result of a success in the law courts! Why success in law should have brought disaster in business may require some explanation. Loog at first only did a wholesale trade and in the second year made nearly a thousand pounds clear profit, to secure which, in the face of possible failure in the court, he registered his business as a limited liability company in 1879.

When in 1882, the House of Lords decided in his favour, Loog determined to copy the Singer Company's plan of opening depots in all the principal towns. Hermann Loog had now a " bee in his bonnet ", he had whacked the great Singer Company and to the day of his suicide he considered this his life's work and sought to apply it in season and out out of season. Where ever Singers had a shop in the South of England, Loog also must have one, yet better located and more elaborate, if possible and the town must be flooded with circular matter referring to the trade name lawsuit. This went on till the depots selling sewing machines and other useful articles for the home numbered 38, including the handsome and capacious headquarters at 126, 127 & 128 London Wall E.C.. Loog worked "like a nigger", as he did to his last day. He lived at Brighton, going down each night at six and leaving home each morning at 6.20, so as to be in town as soon as the first post was delivered. On arriving at London Bridge Station he would cross over to the Turkish Baths opposite and spend a half hour in the rooms, being loaned a private key by the proprietor, as no one was in charge at this early hour of the day. But neither Loog's pocket nor that of Frister and Rossmann could stand the pace and the vanity which had influenced him to neglect his profitable wholesale trade for rivalry with Singers was destined to meet with a rude awakening.

It came about in this way: Hermann Loog, Ltd., was only a "one-man" company, himself owing all the shares but six and in 1885 there occurred some mysterious proceeding which upset the confidence of a couple of the largest creditors, followed by a Press view of a rotary sewing machine, called the "Fox", which the concern was proposing to manufacture, in spite of it conflicting with the interests of Frister and Rossmann, Ltd. In September, 1886, a petition for voluntary winding-up was presented and three months later Frister and Rossmann got a receiver appointed to look after their interests, which were represented by £ 32.000 in debentures. Events now followed rapidly. Just after Christmas, 1887 Loog was arrested, together with his son, a boy of 18 and brought up at the Guildhall, the father on a charge of fraudulently applying £ 8.000 to his own use and of illegal pledging goods belonging to Frister and Rossmann and the son of being an accessory in the culpable omission of the father to make certain entries in the books belonging to Frister and Rossmann. Both defendants were committed for trial, but when brought up at the Old Bailey the jury very soon looked upon the case as one of account and stopped the hearing, returning a verdict of "not guilty". During the next few months Loog tried to get someone with capitol to reopen his old showrooms and offices at 126 & 127 London Wall and start a similar business, as the liquidator of Hermann Loog, Ltd,. had vacated these premises and was declining to do further trade, merely selling off the old stock and collecting the 20.000 instalment accounts.

Mr. George Whight, the surviving partner in Whight and Mann, whose sewing machine business was founded in 1859 and who carried on a sewing machine and musical instrument business at Holborn Bars, E.C., was ultimately induced to listen to Mr. Loog's pleadings and September, 1887, saw the latter installed at his premises in London Wall as manager for George Whight & Co., with, practically, his old range of goods, except another make of sewing machine in place of the Frister and Rossmann. Business, however, was not profitable, although a large trade was done, resulting in a loss during four years of several thousand pounds. Various reasons are given for this. Some say that credit, particularly of jewellery to the working classes, was the cause of failure and others that Loog, who certainly worked very hard, as usual, had his mind too much occupied with lawsuits. Two of these lawsuits arose out of the prosecutions of Loog and his son, previously referred to and the claims were for damages for malicious prosecution. The son's case was taken first, but on February 1st, 1888, the jury found that Frister and Rossmann honestly believed the charge to be true and gave judgment for the defendants, whereupon the elected not to proceed with the second action. In June, 1888, Mr. George Whight, whose connection with Hermann Loog was costing him dearly, was caused to defend an action by Frister and Rossmann of a vexacious character, as the result of consideration shown to Hermann Loog a short time before the liquidation proceedings. Mr. Whight had been in the habit of selling Loog musical instruments and purchasing from him sewing machines and a short time before Loog's crash they had a settlement, which Frister and Rossmann alleged amounted to a preferential treatment of Mr. Whight at the expence of the other creditors. Baron Huddlestone, however, in February, 1890, summed up the case to the jury strongly in favour of Mr. Whight, for whom a verdict was given.

In the meantime, in September, 1888, Loog was dismissed the service of George Whight & Co. and a year later opens a large shop at 34 Newgate Street, E.C., stocking it with Seidel & Naumann sewing machines and musical instruments. Here he was known as the Cooperative Trading Company, but not for long, as within six months he and his partner, the young son of a German banker, got at loggerheads. The way in which the quarrel was carried on would be more amusing had not certain creditors suffered as the consequences. One morning Loog on arriving at his office was told by a stranger in charge that he had been appointed receiver on the application of the partner and that Loog could not remain on the premises. Then followed an application by Loog to set aside this appointment, which was granted and a few days later Loog's receiver orders the partner off the premises. After more litigation it was mutually agreed that a certain solicitor be appointed receiver in the interests of Loog and his partner and within a few days the business was closed. As showing the unsatisfactory nature of these receiverships, we might state that the receiver, as well as the partners, assured the creditors that the estate would realise 20s. in the £., but only after months of weary waiting was 2s. in the £ paid to the creditors and not another penny has since reached them. All applications to the solicitor for a report of the winding-up of the estate have failed to elicit any information, expect the reply that the proceedings had taken place "under the supervision of the Court". We need not say that the assurance underlying this explanation ca only be satisfactory to those who are ignorant of what is meant by the phrase "under the supervision of the Court". Some day Parliament will have to deal with a law which permits a firm when confronted with insolvency and its attendant publicity to have a dispute between its partners, who then apply for the appointment of a receiver, who "opens the oyster", deigning to throw to the creditors a portion of the shell or not, as he sees fit and refusing to give any details as to either the oyster or the rest of the shell.Do not let it be thought that the partners would look after the interests of creditors, they are insolvent and have no further interest in the concern except to get out of it without being branded as bankrupts. Thus honest and fair treatment towards the creditors depends solely upon the receiver, usually a solicitor, who, in spite of the fiction that the assets of an insolvent business belong to the creditors, refuses to give them an account of his stewardships. Of course, there is "the supervision of the Court", but the last man in the world to attach any safeguard in this would be the receiver himself.

To continue our narrative, Loog in July 1890, opens a domestic machinery store at 85 Finsbury Pavement, continuing to act as Messrs. Seidel & Naumann's agent for a few months longer. In the meantime the liquidator of Hermann Loog Ltd., brought an action against Lloyd's Bank, of a peculiar nature. Mr. Loog possessed much personal magnetism and he had succeeded, as no one else had done before or since, in getting that bank to lend him money on hire agreements as security. So much as been borrowed on the

Gresham Street is a street in the City of London named after the English merchant and financier Thomas Gresham.

It runs from the junction of Lothbury and Moorgate at its eastern end, to St. Martin's Le Grand in the west. Gresham Street was created between 1881-1895 by widening and amalgamating Cateaton Street, Maiden Lane, St. Anne's Lane and Lad Lane.

Sewing Machine Gazette