- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

John Brooks Nichols

John Brooks Nichols, son of Jonathan Nichols, was born in South Reading, now Wakefield, Massachusetts, February 8, 1823. He received his education in the public schools. From the age of thirteen to twenty-one he worked for his father making boots and shoes. He then became a cutter for Thomas E. Bancroft, shoe manufacturer in Lynn. After two years he became travelling salesman for a wholesale shoe house for a year. After working six months for Captain Thomas Emerson he became a clerk in a retail shoe store in Cambridge and remained until three years later, when he bought the business of his employer. Two years afterward he sold this business to his brother.

John Brooks Nichols was of a mechanical turn of mind and perfected a stitching machine for use in making shoes. The machines, built in accordance with his designs, were introduced in shoes factories and Mr. Nichols was occupied in instructing operators. He invented a new sewing machine and in 1850 began to manufacture it in a shop in Lynn. He formed a partnership and built the machine in a factory on Hanover Street, Boston.

The firm name at first was Nichols & Bliss, later J. B. Nichols & Co.. A large shop was occupied at the corner of Pitt and Green Street, opposite the Old Revere House, Boston and the business flourished. Mr. Nichols finally sold out to his partners and opened a shoe manufactory in Lynn, in partnership with Charles H. Aborne.

The firm continued twelve years, when Mr. Aborne was succeeded by James W. Ingalls. In 1877 Mr. Nichols retired, though for a time afterward he was interested in manufacturing buffing machines for shoe manufacture. Mr. Nichols resides at 52 Arlington Street, Lynn. He is a Republican in politics and has always been interested in public affairs. He was trustee of the Lynn Five Cents Savings Bank about twenty years. He is a member of the Boston Street Methodist Episcopal Church, has been trustee fifty-one years and is president of the board and treasurer of the board of stewards. He married, at Lynn 1853, Celia H. Ramsdell, born in Truro, Massachusetts, daughter of Rev. William and Celia (Hart) Ramsdell; her father a M. E. clergyman. Children: 1. Ada C. , died 1892. 2. Emma (twin). 3. Ella (twin), living in Lynn. 4. Florence, for a period of ten years and until recently has been president of Isabelle Thalen College, at Lucknow, India. 5. Mary. 6. Child died in infancy. 7. Fred, died young. 8. Charles, died young. 9. William, died young.

extract from:

Genealogical and personal memoirs relating to the families of Boston and eastern Massachusetts

by William Richard Cutter

*********************************************************

extract from:

SHOE MAKING OLD and NEW

by Fred A. Gannon

...An early advertisement of sewing machines, published by I. M. Singer & Co., in a Boston news paper in 1851, attracted the attention of a young shoemaker, John Brooks Nichols, of Lynn. He was born in Wakefield, February 8, 1823.

He learned the trade of shoe cutting of his cousin Thomas Bancroft, who had a shop in the basement of the Congregational church close by Lynn Common. After two years as a shoe cutter, he bought a retail store in Cambridge. This venture failed. Then he saw the advertisement of the sewing machines. Mr. Nichols, an ambitious young man, was seeking some opening with a bright future. He decided that the sewing machine would become of great value. So he bought one of the first lot of 25 machines that I. M. Singer & Co. made.

This machine, Mr. Nichols set up in a shop on Sudbury Street, Boston. He established a contract stitching business, stitching pantaloons on the machine. At the time, the sewing machine had not been perfected for use in stitching leather. Mr. Nichols, a shoemaker by trade, naturally wondered why the machine couldn’t be made to stitch leather. He began to experiment, using scraps of kid leather that he brought from Lynn shoe factories.

He found that his sewing machine wouldn’t stitch leather neatly because the needle was bigger than the thread. The seams were loose and the stitches coarse. But he was of the opinion that his machine could be made to stitch leather as nicely as did the “binders.” To make it do so, he got around to his shop one and one-half hours ahead of time in the morning, and he left it one and one-half hours late, putting in the extra time in his attempts to make his machine stitch leather.

Finding that the needle was too large, he went to the needle manufacturers and got them to make needles of new shapes and sizes. These needles he filed, and even smoothed down with emery paper to get them of the desired small size. He also went to the manufacturers of silk and cotton threads, and got them to make new kinds of thread for his experiments. After months of patient labour, he succeeded in stitching leather on the machine so that its stitches compared favorably with the stitches of the shoe binders. I. M. Singer & Co. undertook to put onto the market machines for stitching shoes.

They sold to three Lynn manufacturers (Scudder Moore, John Wooldredge and Walter Keene), rights to use the machine for stitching leather in Essex County. Mr. Nichols became instructor of operators on the machines used by these firms. He was paid $3 a day for his services, which was twice the wage that he ever received before and a wonderfully high wage for the time.

Mr. Nichols decided that he would himself start a contract stitching shop. The three manufacturers who had purchased the exclusive rights to use Singer machines for stitching shoes in Essex County protested to the Singer Co. against Mr. Nichols starting in business. The Singer Co. declined to let Mr. Nichols have any machines. But he secured a Singer machine that the Singer Company had sold to his cousin, Thomas Bancroft, before they made their exclusive agreement with the three manufacturers. This machine he remodeled so that he was able to use it for stitching shoes. At this time Mr. Nichols first heard of Elias Howe. Howe was just home from his unhappy European trip, and was laying claim to his patent rights. Mr. Nichols went to him in Cambridge and asked for permission to make use of his invention in stitching shoes.

Mr. Howe replied that Mr. Nichols was the first man who had asked permission to use his invention. He furthermore said that William R. Bliss. a Worcester shoe manufacturer, had the rights to use the invention for stitching leather. Mr. Bliss was one of the good friends who provided Howe with money to fight for his patent rights. Mr. Nichols joined interests with Howe and Bliss. Howe. with money provided by Bliss, succeeded in putting a line of sewing machines on the market. These machines were called the Howe improved machine. They were built on designs prepared by Mr. Nichols.

The profit on these machines enabled Howe to employ counsel and to fight his patent suits to a successful finish. Mr. Nichols continued in the machinery business as a partner in the firm of Nichols & Bliss. and later of Nichols & Co. When the sewing machine was new, shoe manufacturers used to visit the Nichols & Bliss store in Boston, inspect the machine and say that it was necessary to give them a practical demonstration. So he employed shoe stitchers to operate the machines in the Boston store.

When shoe manufacturers came in and saw the machines sewing shoes they decided that they must have them, and they bought. Mr. Nichols demonstrated the machine in several communities. In one place, shoemakers, both men and women, crowded around the machine. Mr. Nichols made it run splendidly. The next morning a shoe binder sent word to him that she “would like to hang him to a sour apple tree because his machine would take her work away from her.” She did not foresee that the machine would save her labour and add to her wages.

Mr. Nichols retired from business many years ago. On Feb. 8, 1910, he passed his 87th birthday pleasantly at his home in Lynn. He is a remarkably alert and active for a man of his years.

*********************************************************

LIVING FATHERS OF THE TRADE

Men Who Have Seen Their Pioneer lnventions Perfected by Others

The subject of this sketch has been less known to sewing machine historians than either of the two “living fathers” already introduced to our readers, though his activity in connection with the trade was far greater than that of the others. He did not, like Greenough, conceive an original invention in a strange field, neither did he, like Bachelder, spend years and a small fortune in slow development of the new principle be had evolved. It was as an adapter more than as an inventor and as a manufacturer and dealer more than for experiments that John B. Nichols’ name was associated with the early history of sewing machines. It was as a business man, taking his moderate profit as he went along, not as the proverbial inventor looking for large but uncertain future returns that he was known to us.

Mr. Nichols was born at Wakefield, Massachusetts, Feb. 8, 1823. At the age of 21 years he went to Lynn to learn the shoe-cutting trade with his cousin, Thomas F. Bancroft, then a prominent shoe manufacturer. After two years in this occupation he went into business at Cambridge, first a clerk and then as proprietor of a shoe store which, in the end, was unsuccessful. While looking for other business, in the winter of 1850-51, he saw the advertisement of I. M. Singer & Co., who were just getting their machine into the market, having produced their first “lot” of twenty five machines in the shop of Orson C. Phelps, in Harvard Square, Boston. He then conceived the plan of using the sewing machine in the shoe trade. He bought one of that first lot of machines but failed to get satisfactory work from it on leather, though it worked well on cloth. He accordingly changed his plans and opened a shop in Sudbury street, Boston, where be employed girls for finishing, a man for pressing and an operator on the machine. With this outfit he manufactured pantaloons for the clothing trade. As the result of considerable experiment he in time adapted the machine to leather work.

He was then given a bench in the Singer shop, where he reduced his ideas to practice, adapting the machine to leather work. The right to use the Singer machine for leather, in Essex County, was soon purchased, jointly, by three large shoe concerns: George W. Keene, John Wooldridge and Scudder Moore.

Mr. Nichols was employed to instruct the operators in these three factories, visiting each one daily for several months. For this work he was paid $3 a day, double what he had ever received before when working for others. He next started a small shop in Lynn and stitched shoes for manufacturers. In this shop he had one Singer machine, that had been sold to Mr. Bancroft before the sale of the county right to the three concerns named. He found the business profitable and wishing to increase his plant made application to the three joint owners of the county right. They refused to allow him to use or to have more machines.

Mr. Nichols had, meantime, been employed in the factory of the Grover & Baker Sewing Machine Co. for a time and the knowledge of the business obtained there and in the Singer factory (in early 1852*) made him feel quite independent of the monopoly. It was a pretty large undertaking for a young man with so little means, but he set about to build machines for that stitching plant. He designed and constructed a machine, then having learned of Howe’s claim he applied to him for a license. Howe was than living in Cambridge and Mr. Nichols recalls a walk of several miles through snow-bound streets to find him. He also re- members that Howe told him that he was the first applicant, other manufacturers did not think it worth their while to get his permission to build machines. It seems probable, as will appear further on, that this visit and Mr. Nichols’ entry in this way gave a turn to the whole sewing machine industry, including the supremacy of Howe's patent. It was this machine, designed by Mr. Nichols, that was first sold, in any considerable numbers under the Howe name and it was this machine that interested the capital that enabled Howe to establish his patent claims in the courts. Boston directories of the decade of the fifties have the names of these firms:

Nichols & Bliss, then J. B. Nichols & Co. and last Nichols, Leavitt & Co.

These successive firms manufactured and sold the machine designed by Mr. Nichols and as improved from time to time. Why Mr. Nichols’ name has not become familiar to the public in this connection will appear in a continuation of this article. Asked why he did not take out a patent for his “invention”, he said: “There was no new principle disclosed in it. It was but an adaptation and rearrangement of known means for accomplishing the purpose”. He did not think it a proper subject for a patent. And yet, since that time many hundreds of sewing machine patents have been granted that had but a fraction of the originality that appeared in this design which the modest author thought unworthy of the title of “invention”. There was, however, no occasion for a patent, as his relations with Howe and through Howe with the “Combination”, gave all the protection that any additional patents could have given.

(Continued from Issue of April 25, 1904)

Reference has already been made to Mr. Nichols’ designing, he will not have it inventing a sewing machine and to his application to Mr. Howe for a license. Following is a portion of a letter from Mr. Nichols, not written for publication but introduced in part as an interesting statement that sets forth the facts in a condensed and perspicuous form that carries the impress of a sound memory and a vigorous mind. After arranging with Mr. Howe the price and terms of royalty to build machines under his patent, I informed him that I intended to use and sell to boot and shoe manufacturers, to use in stitching kid, morocco and other leather. Mr. Howe said that he had sold this right to Wm. R. Bliss, of Worcester and offered to introduce me to him if I would meet them in Boston the next Saturday, which I did. Mr. Bliss wanted me to bring my machine up the next week. I did so and he appeared to be pleased with it and made another appointment for me to meet him.

Mr. Bliss then proposed a partnership. I was to put in my machine and he was to furnish the capital to carry on the business, also to sell me one-half of the New England rights under the Howe patent; I to pay him out of my share of the profit of the business.

We soon made a contract with Rufus and Martin Leavitt for a lot of cylinder machines, for leather work and another contract for a smaller machine without a cylinder, with another firm of machinists.

We soon hired a store on Hanover street, near the American House, where shoe manufacturers met the trade every Saturday. Many called in to see the “Howe”, as we called them machines and we began to get orders and soon had a good and increasing business, getting $125 for each machine, (the current price). Then Mr. Howe began suits to enforce his patent and when his lawyer asked for $8.000 for fees and court expenses, Mr. Howe, without other means, offered Mr. Bliss one-half of his patent if he would furnish that amount.

Mr. Bliss’s previous contract with me prevented him making this arrangement. To remove the obstacle Mr. Bliss offered me the whole of the manufacturing business if I would relinquish my claim on the New England patent rights and he would furnish all the money I needed to carry on the business, at 6 per cent. He said the patent would be of no value to Mr. Howe, to himself, or to me, unless this suit was brought and the patent established by the decision of the court. My sympathy for Mr. Howe and the realization of the situation caused me to decide to accept his offer, as the sale of machines had become profitable and was increasing.

After the suit was decided in Howe’s favour, Singer, Wheeler & Wilson, Grover & Baker and others came on to Boston and made the best terms they could with Messrs. Howe & Bliss, agreeing to pay a royalty of $10 each on the first thousand machines made; $9 for the second and $8 for the third, a sliding scale to $3 a thousand, which was to be paid during the life of the patent. I understood they made a hundred thousand dollars the first year, thus bringing Mr. Howe from poverty to affluence and a fortune to Mr. Bliss for a small investment.

Mr. Bliss only lived about two years to enjoy his good fortune, leaving his estate to his son who was about twenty years of age, a second wife whom he had married while in company with me and probably some to his two sisters who were his housekeepers in Worcester.

His son, Wallis, died within two years of his father’s death and the patent was resold to Mr. Howe making him the sole owner again. I have written this simply to explain the case, not intending it for publication unless you find the facts can be used to make your article clearer.

(Continued from issue of May 25, 1904)

The story has already been told, how Mr. Nichols, in partnership with Mr. Bliss (1852-53), who became Howe’s partner, manufactured and sold sewing machines in Boston, advertising them as the “ Howe” machine.

This machine, as first designed by Mr. Nichols, was specially intended for leather work and was of the cylinder form which has continued to this day as a type adapted to certain lines of manufacture. It will also be remembered in connection with the machine made and sold by A. B. Howe, (brother of Elias, Jr.) which had a reputation in the shoe-fitting trade.

Nichols’ sewing machine went through various changes, as made by and sold by Nichols & Bliss (1852-53), J. B. Nichols & Co. (1854-55), Nichols, Leavitt & Co. (1855-56), Leavitt & Co. (1856-65), Leavitt Sewing Machine Co. (1866-67), Leavitt & Brant (1868-78).

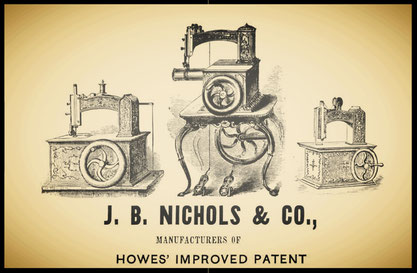

From an old wood cut on a fragment of an early business card we reproduce one form in which this machine was put on the market. For family use it was constructed with a flat bed. Thus it will be seen that the form in which the “Howe” machine first got into the market was that given to it by Mr. Nichols and suggested to him by his experience with the other makes of machines that had just begun to get into public use.

Mr. Nichols disposed of his interest to his partners, the Leavitts and engaged in the manufacture of shoes, in Lynn.

The Leavitts continued business for many years, introducing new styles of machines. When the Howe Machine Company put a machine of their own make on the market F. W. Nichols, brother of the subject of this sketch, became their New England representative, with office in Boston and was widely known to the past generation of the trade.

In the manufacture of shoes Mr. Nichols was long a partner with his cousin, Charles H. Aborn, who at the time of his death, in February last, was the oldest active shoe manufacturer in Lynn. Later he was of the firm Nichols & Ingalls.

Twenty-five years ago he retired from active business and is living quietly at Lynn, finding much enjoyment in the care of his property interests and the affairs of his home and church. In November last, Mr. and Mrs. Nichols celebrated their golden wedding in a very happy manner, surrounded by relatives and friends, including four living daughters.

Sewing Machine Times July 10, 1904

*

Men, Women and Work: Class, Gender and Protest in the New England Shoe Industry, 1780-1910 by Mary H. Blewett

On May 18, 1853, Elias Howe granted his first royalty license to Wheeler, Wilson & Company. Within a few months licenses were also granted to Grover & Baker, A. Bartholf, Nichols & Bliss, J. A. Lerow, Wooldridge, Keene and Moore and A. B. Howe, the brother of Elias.